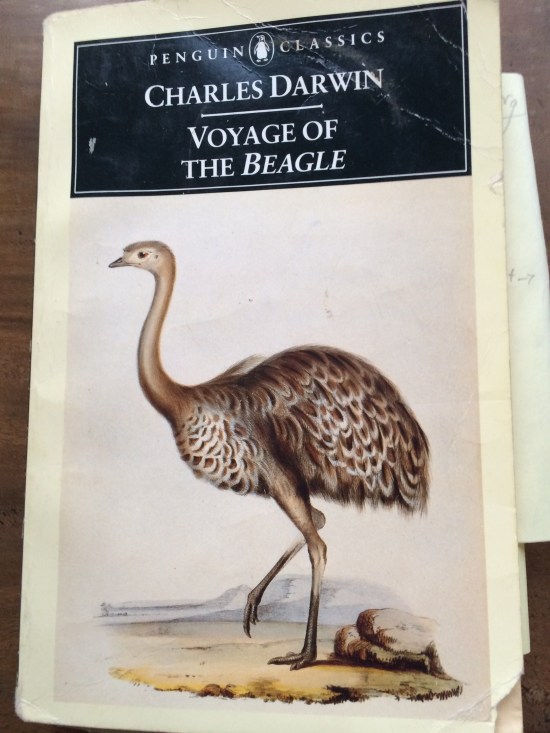

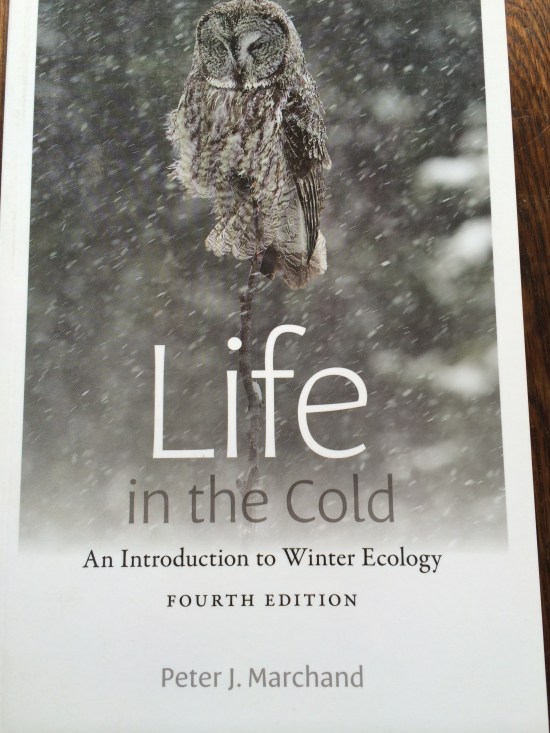

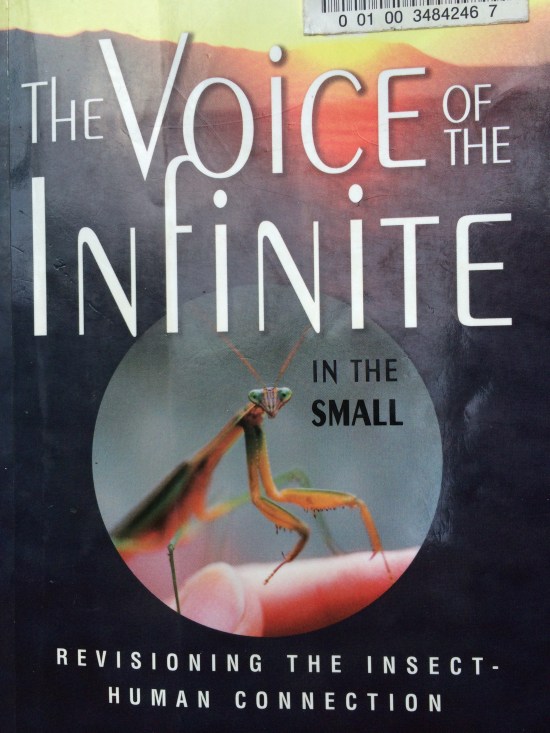

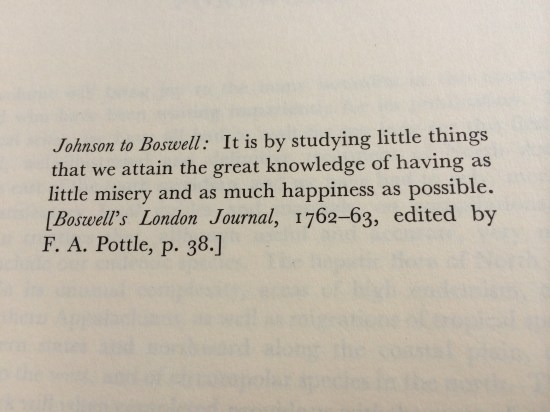

Dawn at the shore of Cayuga Lake, at Aurora, New York, thick with little ice floes, where Canada geese “sleep” at night. These were the conditions during much of January, February, and March 2015.

I never thought I would be moved to write about Canada geese, though naturalists are supposed to be interested in everything, and I am, but I have, unfortunately, shared many people’s misperceptions that these large, melon-shaped, waddling birds have more obnoxious qualities than pleasant ones. They can’t sing, and they take over lake shores leaving copious droppings. This is all wrong headed. They can’t sing, but they can talk in an interesting fashion, and their droppings are very “clean,” really just grass pellets.

Since Thanksgiving my husband and I have slept a dozen or so nights in Aurora, New York, just 250 yards from the shores of Cayuga Lake, one of the beautiful Finger Lakes in upstate New York. Each night the noisy conversations of the geese on the lake have made sleeping through the night impossible. As the woman at the coffee shop said, “It is a great cacophony.” One dozes, rolls over, opens an ear. Yes, they are still squawking at top volume…throughout the night. My question is, what are they talking about? Like most people I love the sound of the melancholy honks of migrating geese and the sight of their strong pinions flapping rhythmically like oars in the sky. But these geese are neither migrating nor mating. They are temporary residents of Aurora all winter, feeding in the cornfields nearby by day and chatting near the shore of the lake by night. Soon they will go north to breeding grounds that they return to year after year, I fantasize perhaps even to Teshekpuk Lake in Alaska.

I asked my husband what he thought the subject of their extensive conversations might be. His answer was quick. “It’s bedroom talk,” he said. “But it’s not mating season yet,” I said.

I would probably not have become obsessed with finding an answer if not for a recent reading of What the Robin Knows by Jon Young. Young, mentored by tracker Tom Brown in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey, has become a leading authority on bird communication.

He writes, “Observers of bird language listen to, identify, and interpret five vocalizations: songs, companion calls, territorial aggression (often male to male), adolescent begging, and alarms.” His thesis is that songbirds have a number of specific vocalizations and if we humans pay attention we will know more about the world going on around them/us, the point being that them/us are One.

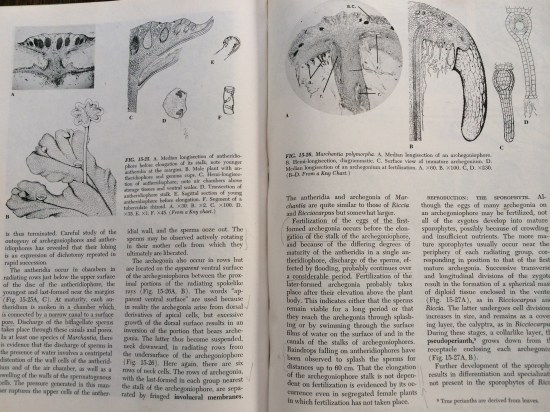

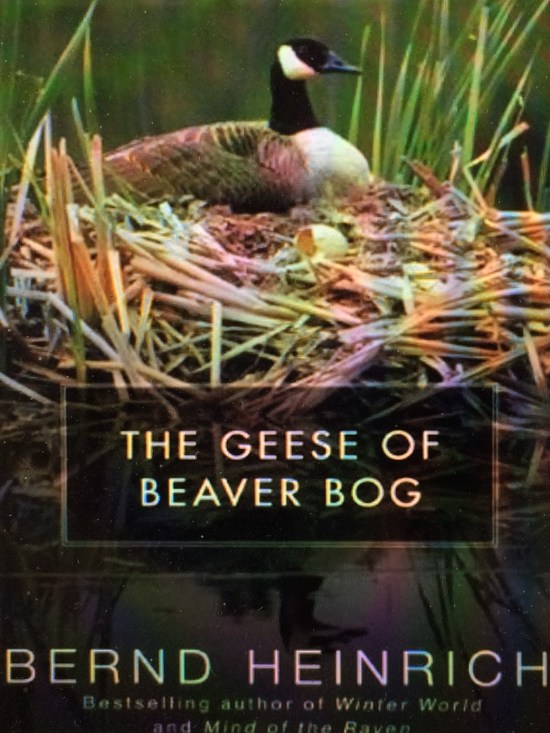

My search for an understanding of what they need or want to communicate about all night long has led me on a wild chase into goose literature (the nights were way too cold and too dark for first-hand observation, and the geese sensing an interloper would have altered their talk). First, two points: (1) geese are perhaps second only to humans in their level of communicativeness, and (2) geese act purposefully, their vocalizations often indicating the purpose or concern at hand. My exploration led me eventually to naturalist Bernd Heinrich’s book The Geese of Beaver Bog. He makes point #2 when talking about some unusual activity of Peep, the goose friend he observes in the book: “It is presumably not without reason. No goose behavior is.” This remark made me sure that the deafening nocturnal chatter of the Canada geese by the shores of Cayuga Lake in Aurora has a purpose.

Bernd Heinrich reports on his observations of Peep and Pop, a goose and gander who nested at the edge of one of the beaver ponds near Heinrich’s house. A dramatic account, as he is often dashing around sharing in the hardships of Peep and Pop.

Canada Geese are said to have at least 13 kinds of vocalizations, though one source puts the number at several dozen. Some of these can be heard on the Macaulay Library of biodiversity audio and video recordings, part of Cornell University’s Laboratory of Ornithology. Under calls, they list “various loud honks, barks, and cackles. Also some hisses.” Peep, Heinrich’s part tame/part wild goose friend allowed him to observe intimate details of her life with the completely wild gander Pop. He writes of one of her sounds, “She closed her eyes and made barely audible low grunting sounds when I walked up to her. If sounds have texture, these were velvet.” His book gives one an entirely new appreciation of the intelligence and deep heart of this species. A recent youtube video made in February 2015 makes me think of Peep and Pop. It captures some of the evocative and tender impressions that I gathered from Heinrich’s book.

A comprehensive survey of the life history of Canada geese (Branta canadensis) by State and Federal Licensed Waterfowl Rehabilitator Robin McClary describes their strong social bonds. McClary writes that Canada geese are “loyal and emotional towards each other,” a clue to their frequent vocalizations. They mate for life (though Heinrich describes a “divorce” in The Geese of Beaver Bog) and congregate in family groups. If first-time parents are negligent towards their progeny, older, more experienced adults move them to foster care. Extended family groups congregate and stay together until the next mating season, with large family groups showing dominance over small ones. McClary writes that mating bonds are sometimes established on wintering sites (clue). McClary describes the considerable range and subtlety of their vocalizations:

“The gander has a slower, low-pitched “ahonk” while the goose’s voice is a much quicker and higher-pitched “hink” or “ka-ronk.” Mated pairs will greet each other by alternating their calls so rapidly that it seems like only one is talking. The typical “h-ronk” call is given only by males. Females give a higher-pitched and shorter “hrink” or “hrih”. Pitch also changes depending on the position of the neck, and the duration of the call varies depending on context. Dominant individuals are about 60 times more vocal than submissive flock mates. Canada geese calls range from the deep ka-lunk of the medium and large races to the high-pitched cackling voices of smaller races. Researchers have determined that Canada Geese have about 13 different calls ranging from loud greeting and alarm calls to the low clucks and murmurs of feeding geese. A careful ear and loyal observer will be able to put each voice to the honking goose/geese.

Goslings begin communicating with their parents while still in the egg. Their calls are limited to greeting “peeps,” distress calls, and high-pitched trills signaling contentment. Goslings respond in different ways to different adult calls, indicating that the adults use a variety of calls with a range of meanings to communicate with their young. The goslings have a wheezy soft call that may be either in distinct parts – “wheep-wheep-wheep” – or a drawn out whinny – “wheee-oow”. Just as in adolescent people, when the voice changes as the goose matures, it will often “crack” and sounds like a cross between a honk and a wheeze. This will be noticeable when the goslings are becoming fully feathered and starting to use body movements to communicate. When a flock gets ready to take off and fly away, they will usually all honk at the same time. The female makes the first honk, to indicate it is time to go, while the rest of the flock will chime in all together. The female leads the flock away in flight.”

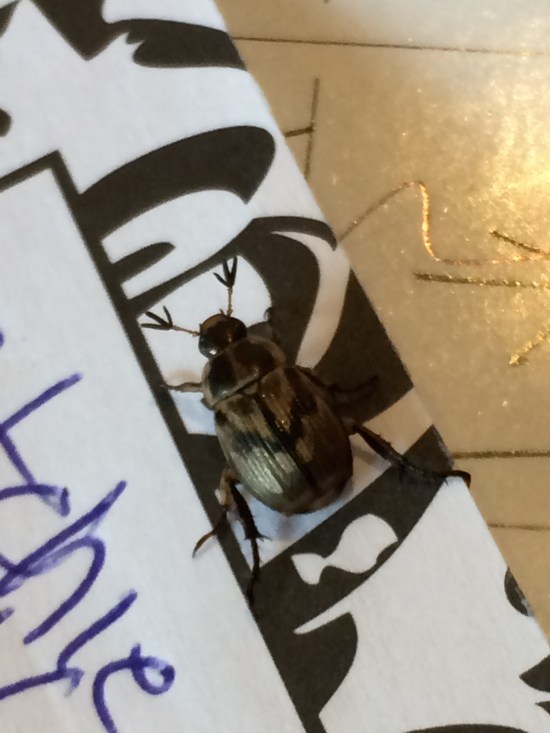

These descriptions were music to my ears as I realized how interesting a subject I had found through pursuing a naturalist’s query. My sojourn by the shores of noisy Cayuga Lake over, I feared opportunities for first-hand observation were over as well. However, I soon happened to find myself among the Canada geese again at my son’s college golf tournament in Hellertown, Pennsylvania. While having my morning coffee at a Panera in a busy intersection in Bethlehem, PA, I noticed a set of framed photos to the left of the cash register featuring Canada geese.

I took a close up of their photo of goslings protected under feathers of mother goose.

Then I looked outside the window and saw a goose or gander in the median strip of the busy intersection.

I did some further investigations (it was a very hard area to drive in, so the geese have quite an advantage in flying), and found a small conservation area (a small swampy stream) across the highway from the Panera, where a family group browsed. Parking was not easy, so I observed from the car window. Also, I didn’t want to disturb them. If they had mastered this busy environment, they didn’t need a stranger upsetting their routine. They are wary birds, very attuned to human behavior.

On to the golf course I went, where, happily, I found that Canada geese were plentiful at the various ponds and other water hazards.

By now I had learned enough about Canada geese to be respectful and a somewhat savvy observer. I did not try to get close enough to take better photos, and I avoided disturbing their feeding. All the geese I encountered had paired off, with the gander acting as lookout for the goose, so she could browse undisturbed. The pairs remained silent for the most part, rarely a honk or hiss. Things are relatively serene now, as nesting has not yet occurred, and the geese seem to know that golfers startle easily and need quiet surroundings. I enjoyed watching the pairs and noting how their behavior was like that of Peep and Pop, as described by Heinrich in The Geese of Beaver Bog.

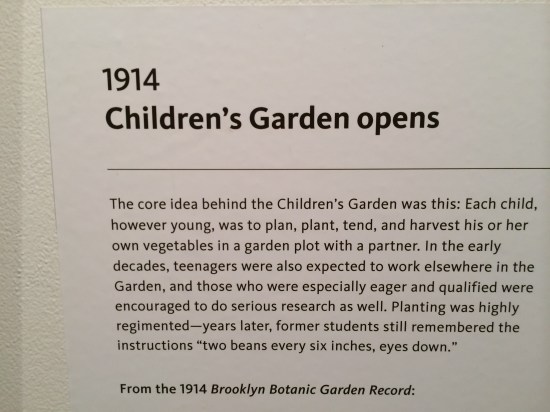

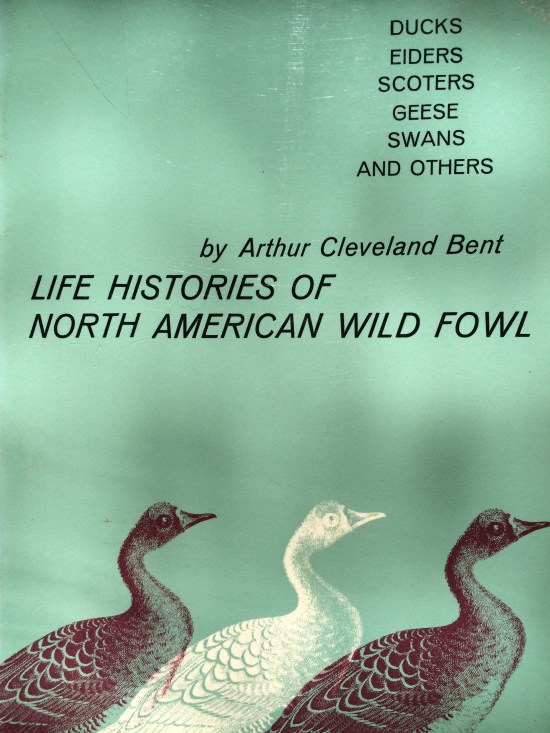

One of the sources I consulted for this piece. This is part II, of one of the 20 volumes in the magisterial work on North American birds by Arthur Cleveland Bent, who quotes freely from John James Audubon’s spirited writing on Canada geese.

I have done a lot more research than I can report on here, but clues abound in answer to why the Canada geese talk through the night in their midwintering grounds at Aurora, NY. Yes, it could definitely be bedroom talk as my husband suggested. McClary mentioned that the choice of mate for first-time maters often occurs in midwinter. Also, it could be that family groups become separated during feeding at the cornfields during the day and just need to sort themselves out at night, with the larger family groups jostling for space over the smaller family groups. And, as McClary noted, dominant individuals talk 60% more than less dominant individuals, so the gathering off the dock may have been full of dominant individuals. Maybe they were complaining over the ice floes, the cold, the state of the cornfields. Maybe….

The last night that we stayed in Aurora, I placed ear plugs by my bed, but did not use them. I couldn’t do it. I wanted to listen and imagine even if I could not understand.

(I have posted on youtube a video recording, courtesy of David Fernandez [husband], of the vocalizing Canada geese. Quadruple the volume and you will have some sense of the “great cacophony.”)