In 2007 black locust trees (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) in Ithaca, New York, flowered profusely. I walked about admiring them, did some research, and wrote an essay, which I stored on my computer because I had nowhere to send it. It has happened again. The flowering of all of the black locusts in Ithaca in 2013 is noteworthy, divine in fact I would say.

Now that I have a blog, which is in part for me a place to admire, explore, and lament upon (not too often I hope) topics that interest me as a naturalist and writer, I have updated my previous piece, and in doing so experienced the black locust in unexpected ways.

Botanists have long studied and described noteworthy flowering patterns in trees. One pattern for a flowering individual is the production of flowers over an extended period, while another pattern is the production of many flowers all at once over a short period of time. The latter is called mass flowering. A plant’s flowering “strategy” makes a difference when it comes to attracting pollinators. Pollination is necessary to ensure survival of the species that relies on seed production to reproduce.

Sometimes all the individuals in a population of a species inhabiting a wide area flower all at the same, and this is also called mass flowering. The term is often particularly applied to the very tall dipterocarp trees of Southeast Asia, which display communal, synchronous flowering. What is unusual in this behavior is that many different species of dipterocarp trees flower at the same time. It is an interspecies rather than an intraspecies phenomenon. (An analogy might be that it’s like a group of ethnically diverse people in 10 counties in New York State deciding to get married at the same time? I have not thought this analogy through, but offer it as a stimulus to further thought on the reader’s part.)

An even more unusual, and different, case of mass flowering occurs in bamboos, which wait a long time to flower (sometime 100 years), flower all at once, and then die, which is not a good time for the panda bears.

The case of the black locust in 2007, and now in 2013, doesn’t fit any of these scenarios—because the flowering period is normal, i.e., not a short burst or a long burst. It is simply a very good year for flowering and all the black locusts are into it. Whether the physiological basis relates to optimal conditions in the fall (when many flower buds are “set” in plants), or to optimal conditions in the spring, is beyond my botanical knowledge at this point. What I have observed now is that ALL the black locust trees are flowering, from gaunt, misshapen “elders” to graceful, young “adolescents.”

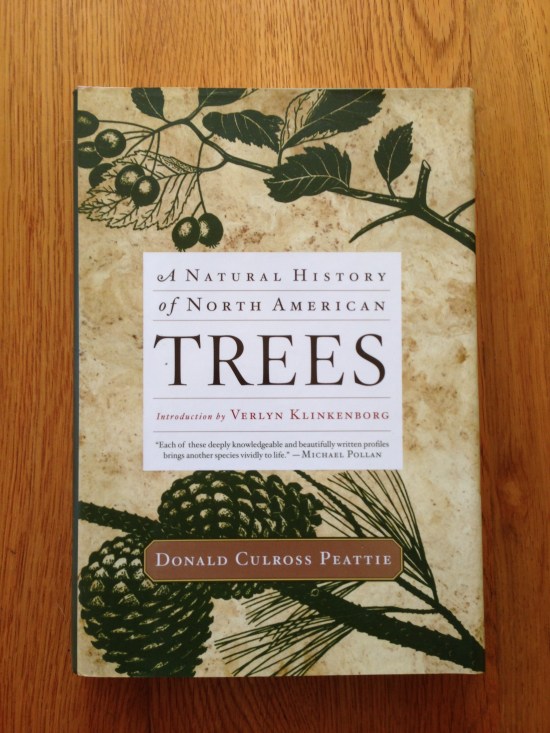

The black locust is a true American hero. Native to the southern Appalachians and the Ozarks, it was the first North American tree species to find its way to Europe via seeds sent from Louisiana by either Jean Robin, herbalist to Henry IV of France, or his son Vespasien Robin, between 1601 and 1636. Donald Culross Peattie, one of the very best writers about North American trees, gives an informative account in his A Natural History of North American Trees, originally published in two volumes in the 1950s and reprinted by Houghton Mifflin with an introduction by Verlyn Klinkenborg in 2007. Everyone in the United States should have a copy–and read it. The trees of North America have sustained an immeasurable part of American culture and civilization.

Peattie, who made an interesting transition in his educational life, from being a student of French poetry at the University of Chicago to being a student of the botanist Merritt Fernald at Harvard, describes the ways in which the history of trees and people intersect. America could not have sustained itself without native trees offering support to the early colonists, who were a curious mixture of the privileged and the down and out, according to Peattie. Not a handy lot as far as the building of shelters.

He writes that the early settlers at Jamestown had no idea about how to construct a log cabin (that was an innovation we owe to the Swedish apparently). A century after the founding of Jamestown, the early Virginians were still struggling. Peattie quotes Mark Catesby, a British naturalist, who described what was going on at the time: “ ‘ Being obliged to run up with all the expedition possible such little houses as might serve them to dwell in, till they could find leisure to build larger and more convenient ones, they erected each of their little hovels on four only of these trees (the Locust-tree of Virginia), pitched into the ground to support the four corners; many of these posts are yet standing, and not only the parts underground, but likewise those above, still perfectly sound’” (Peattie, p. 336). The black locust, a tree that supported a country in its imperfect infancy: hovels supported by posts of stout heartwood.

Black locust trunks are almost entirely heartwood, which is of very high quality in terms of stiffness, durability and strength. Peattie writes, “It is the most durable of all of our hardwoods; taking White Oak as the standard of 100%, Black Locust has a durability of 250%.” Unfortunately, in this country a little boring beetle (Megacyllene robiniae) has ruined the reputation and usefulness of black locust lumber. Populations in Europe are free of the infection, however.

Contentious William Cobbett became the great black locust seed entrepreneur of the early 1800s. He started a plantation on Long Island to supply the British Navy with treenails.The wood makes supremely durable treenails, which were used extensively at the time in shipbuilding. In water, they swelled into a tight fit and never rusted. The winning of the War of 1812 has been attributed to the strength of the winner’s treenails. Farmers today still fight over a good source of black locust posts for fences. Read Peattie to find out why Cobbett had to flee the United States and why he took the coffin, and corpse, of Thomas Paine with him.

In my research I found a Hungarian website with an article by Bela Keresztesi, Director-General of the Forest Research Institute at Frankel Leo University in Budapest. He writes that black locust and poplar are tied for second place as most extensively planted in the world (eucalyptus is in first place). There are about a million hectares of manmade black locust forests on the planet (a fact I gathered in 2007, but have not verified in 2013).

But what is new in 2013 for me and the black locusts? Although having lived more than 30 years in Ithaca, my heartwood was formed in Virginia. Maybe that is why I feel such an affinity to the “Locust-tree of Virginia.” I do know from my experience growing up in Vinegar Hollow in Highland County, Virginia, that locusts often seed themselves into groves. In other words, the peas from their pods (they are a leguminous species) don’t stray too far from the parent trees. The seedlings grow up in near proximity to the parents, and thus groves are formed. The farm in Vinegar Hollow has a very old locust grove, with trees gaunt and blasted by time and weather, and a young grove high on Stark’s Ridge where slender young trees vie for the sky light. I remember walking in the old grove with my father. He loved the locust trees. I see his fingers touching the places where sheep rubbed their rumps against the deeply ridged trunks. He pointed out to me how the lanolin of their wool burnished the bark. That is the grove that will live in my memory forever.

In 2013 I decided to do less Internet research and more gathering of information from direct experience, having been influenced by a recent reading of naturalist Robert Michael Pyle’s essay “The Rise and Fall of Natural History,” whose subtitle is “how a science grew that eclipsed direct experience.” He laments the loss of bodily experience outdoors in the company of other species in a nonmanufactured landscape. Somehow I had to get closer to the black locusts of Ithaca.

There is a grove that I have admired for years at the corner of 96 and Bundy Road. This past Saturday morning I decided to try a little paparazzi-style photography. At 7:30 am I drove up a long driveway to get an overview of the grove, realized it was a personal residence, and so retreated to the main highway, 96, and parked in a pull off area and clambered into a ditch and up a steepish hillside, and thence to a closer view. The light played over the grass at ground level and the trunks of the trees, creating sinuous bands of dark and light. Graceful and commanding, the trees owned that hillside and the landscape. The land was theirs, and the sky also, it seemed as from my vantage point the branches grew up, up, and up into the blue sky and white clouds. I stood there in awe, though I was awkwardly situated, worried that I might have touched poison ivy in the ditch. I don’t mean to undercut the beauty of my direct experience; it was exhilarating, but a case of poison ivy causes me to lose my sanity so I had to cautious. That was Saturday, early morning.

The end of the story concerns another kind of first-hand experience. Sunday night my husband came home with an armful of branches full of racemes of black locust flowers. Their fragance filled our kitchen. David was late for dinner as usual because he had been in the country mowing. Tractoring along the hedgerow beneath the black locust trees, hungry, he grabbed clusters of blossoms and ate them. Caution set in quickly, however. Worried that he might be poisoning himself, he consulted Google on his cell phone and found that locust blossoms are edible! Our dinner of rice and leftovers took on a festive air. We threw handfuls of the blossoms on everything. Douglas, who is 20, refused to eat any on principle, but Charlotte, who is over 20 and interested in herbal remedies, began ingesting flowers enthusiastically. She even found a recipe for black locust soup! They say one way of understanding a species is to eat it—with reverence and with love.

The next thing I must do is wander at night in a locust grove with a flashlight. Peattie writes that “Among the Locust’s numerous familiar charms, most famous is the so-called sleep of the leaves. At nightfall the leaflets droop on their stalklets, so that the whole leaf seems to be folding up for the night.” He has more to say on the subject, and I will too after some direct experience!

Note: The noted naturalist Marcia Bonta (read her column “Flowering Trees of Spring” available on her website, http://www.marciabonta.com) writes about a fine display of black locust flowering on her Pennsylvania mountain top in 1999, the finest then in 27 years.