I know it’s winter, and I love the colors of winter, the grays of tree trunks and the white of snow and the beige of beech leaves, but I am thinking about a bouquet of flowers.

I have a big, black wolf of a dog, a Belgian Shepherd named Belle, who needs to be reminded often that she is a dog and not leader of her human pack, so I take her to doggie day care once a week. There in a pack of 17 or so dogs she learns that a pecking order is the name of the game for most creatures on Earth. Pam, who runs the doggie day care, is in my pantheon of heroines. There is no question that she is leader of the pack of 17 who run and romp and bark and snarl in the fields by the barn. It helps that she is tall. But she has the voice as well. When she says “Knock it Off,” the most overexcited, tooth-ey cat killer (there are such dogs there, but Belle is not one of them) wilts, sitting back on his or her haunches, ears back, the picture of canine contriteness. Pam understands each dog, adapting her approach to his or her strengths and weaknesses. Assertiveness blended with acceptance and compassion is an art. Even though I can’t say “Knock it Off” the way she does, I have learned from her.

Pam is also good with flowers. They abound every which way on the property, in beds along the driveway past the trailer to the barn, around trees, hanging from vintage contraptions on the barn itself. Huge barrels of dahlias guard the fence of the first pen. Though I was in a rush to get to my 8 am class, I stopped to admire a 4-foot tall dahlia, its flowers absolutely off the charts in size and pinkness.

“Hang on a sec. Let me grab a blossom for you,” Pam said. She picked the biggest, pinkest blossom, her large, work-hardened hands turning the flower to face upward.

“But, do you like this lavender one?”

“Sure.” She plucked it.

“What about this rose one?”

“Sure.” She plucked it.

“You need this one with the ruffley edges.” She plucked it.

Soon enough I had a bouquet of 8-10 blossoms, all in different hues, pink lavender, pink white, red red, all with varying petal shapes, from frilled to square cut.

“Go, girl!” she said. I did. I dashed over hill and dale to the Writing Department at Ithaca College, found a vase in the copy room, and situated the bouquet in my office. I considered carrying the vase to my classes to freshen the blah bureaucratic ambiance of the classrooms in which I was teaching, but decided I couldn’t handle it as I am also a bag lady (a literary one, though).

Upon return to my office I found the bouquet alive and well. In fact, there was a large green and white caterpillar munching on the largest dahlia, making great inroads into a lovely pleated petal while producing sizeable chunklets of poop (technical term here is frass) one after another as I watched. And a demure ladybug, skimming lightly over an adjacent petal.

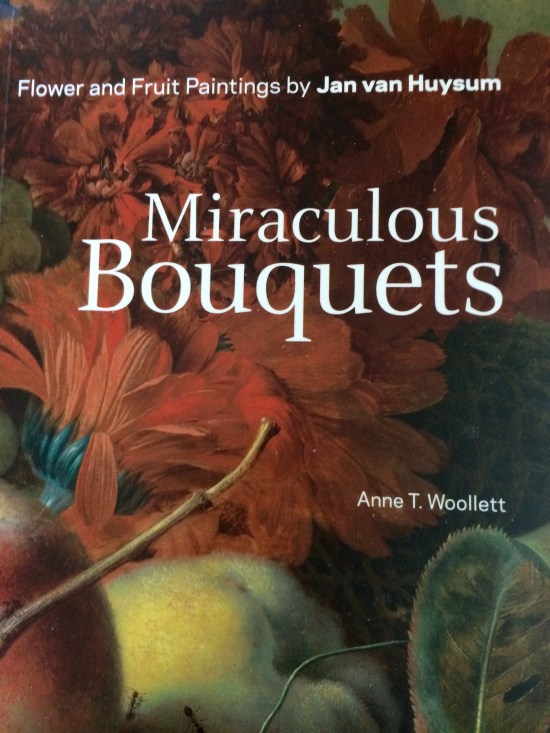

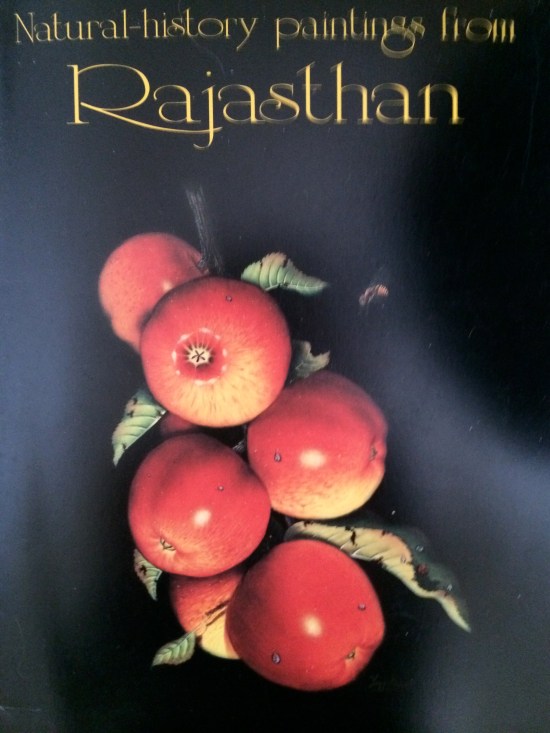

Pam’s bouquet made me think of the little book I couldn’t resist buying (book jacket below) as a potential gift for someone, but have not parted with yet. I have always been attracted to the contradiction inherent in still lifes—the serene perfection of the still representation vs. the attempt to capture life in motion—the water droplet about to roll off a leaf, a caterpillar poised for the next bite.The Dutch still life painters of the 17th century, like Jan Van Huysum (1682-1749), often painted the insects that lurked on the bouquets they tried to capture so realistically. Anne T. Woollett, author of Miraculous Bouquets: Flower and Fruit Paintings by Jan Van Huysum (The J. Paul Getty Museum) writes, “Although the brevity of life was not their primary theme, the curling petals and bent stems of Jan’s lavish bouquets, as well as the exposed fruit seeds and gnawed flesh, convey the passage of time.”

Painters from many cultures have labored over these kinds of still lifes, pushing technique to achieve ever greater perfection of representaton. Huysum painted on oak and copper, had special minerals ground for his paints, and overlay the images with yellow glazes. James J. White and Autumn M. Farole in their commentary for the exhibition catalogue shown below (given to me by a friend, which I can’t part with either) describe how Mahaveer Swami, a painter of natural-history miniatures in Jaipur (the Pink City of Rajasthan, India), uses a paintbrush that is just a single squirrel hair to achieve precise details. I love the work of these natural-history artists, while hoping that each brush stroke is a tribute to the life form, bug or flower, that posed as model. In writing here I realize that I am engaged in representation, when the true gift of the bouquet was life in motion.

Book jacket of exhibition catalogue published by Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie Mellon University, 1994. Cover, by Jaggu Prasad, is titled “Cluster of Apples with Insects.”

I rushed home with the bouquet, placing it in my garden to liberate the caterpillar and the ladybug. I watched it age day by day. The water grew green with algae. The petals lost color, drooped, and fell. The bouquet did not look less beautiful to me. It represented a gathering of experience: dogs scampering along the fence line trying to figure out what the humans were doing, Pam’s large but gentle hands turning each blossom this way and that, and the surprise of the caterpillar and the ladybug.