Cows eating their way to Starks Ridge in the cool of early morning.

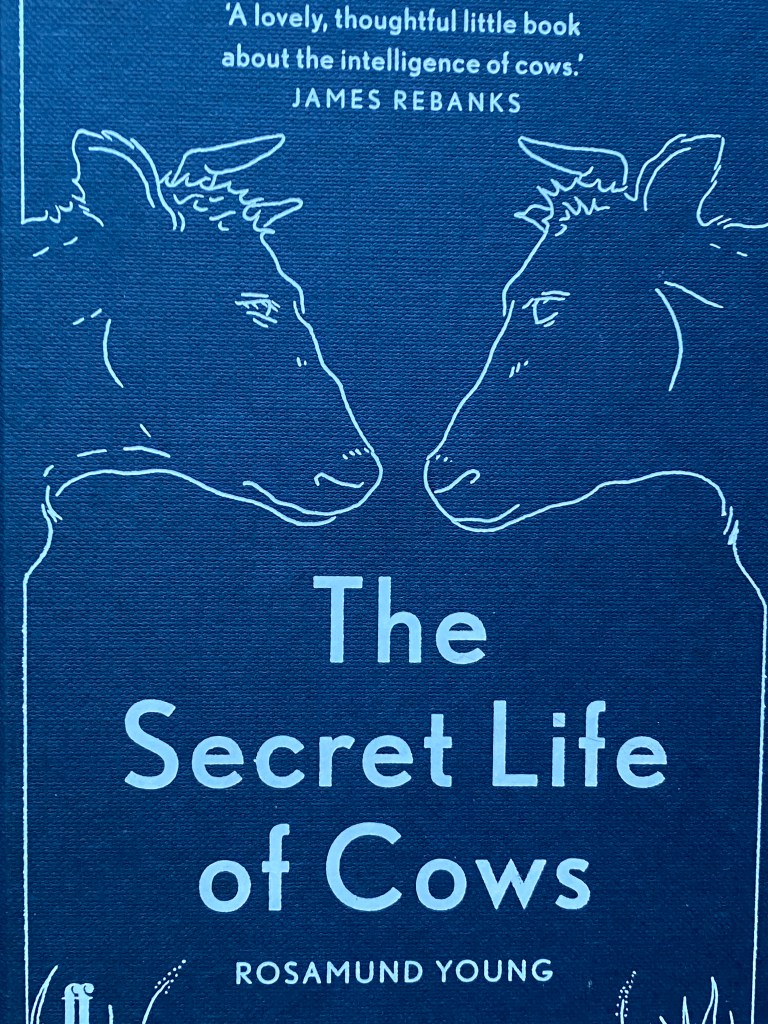

I arrive back in Vinegar Hollow to experience a week of June in Highland County, Virginia, at the farm that my parents bought in 1948. Things seem tranquil on the first morning as the cows move slowly across the hills chomping at the new grass, but soon enough a news story develops.

Early morning: four incarcerated cows and a cat on a fence post.

When Mike came to feed the barn cats the next morning, he noticed ear tags that didn’t match those of his herd. Two cows and two calves, not necessarily belonging to each other, which is problematic for all concerned, had strayed through an open gate from a neighboring property the day before, setting off quite a kerfuffle in the home herd. There was a tremendous bellowing by the trough all day as the cattle tried to figure out who belonged where. In the evening the owners rounded up the strays but couldn’t get them back over the Peach Tree Hill before dark so they spent the night cooped up, like chickens you might say, which did not agree with them. They had plenty of water in the trough, but the grasses on the other side of the fence smelled so sweet. Their longing for freedom intensified over night and they stared at me intently as I strolled with my morning coffee, hoping I was the one who would free them. I told them Corey and Miranda would come soon.

I remembered the time my sister and I slept overnight outside in our sandbox, which had been converted into a tent. We woke up in the early morning when the large head of a large deer poked through the blanket over the sandbox, sniffing, nuzzling, and terrifying us. It turned out be to a pet deer that had escaped its owner. This is what I mean by news stories on a farm.

Nearby I watch the daily progress of the wild cucumber creeping out of the gone-wild calf nursery. This enclosure, my mother’s old vegetable garden, has metal hoops that are covered in winter with canvas to protect newborn calves that have been booted out of the barn to make way for new arrivals–in the too-cold of their birthing season.

Wild cucumber vine creeping over the wall, tendril by tendril.

It’s over the wall!

Still drinking my coffee, I watch the blue-black butterfly that comes jogging around the house every morning and afternoon visiting the same patch of scat, which has been rained on so often that it must seem fresh. This is probably the black swallowtail mimic that has no tails, the Red-spotted Purple (Limenitis arthemis astyanax).

Red-spotted Purple on scat in garden lawn.

This individual has come to seem like my personal friend. I have chased around after it and found that its behavior fits that described for this species–it enjoys scat, gravel roads, and roadsides.

The butterfly has made its way to our gravel driveway. Photographing butterflies is frustrating for the amateur. This is not sharp, but finally I see the “red” spots at the extremities of the upper wings. I didn’t notice them at all while observing the constantly moving “flutterby.”

Underside of the Red-Spotted Purple found by the side of the road near the apple orchard in Vinegar Hollow. It was killed, mostly likely, by my car or Mike’s as very few others travel this road. Soon I started noticing dead Red-spotted Purples on Route 220 north and south to Monterey. Their penchant for frequenting gravel and roads is not healthy.

The Red-spotted Purple has found fame in the hands of writer May Swenson, author of the poem “Unconscious Came a Beauty” written in the shape of the butterfly that alighted on her wrist while she was writing one day. It is a delicate poem full of stillness until the last line, “And then I moved.” She was fortunate to have this experience, and we are fortunate to have her poem. The hollow seems to be full of Red-spotted Purples this year, and there is much to learn about them. There are good observers out there, like Todd Stout, who offers a youtube video on identifying the hibernacula of this species. A hibernaculum is the overwintering curled-leaf-like home of the caterpillar, beautifully camouflaged to avoid notice. It is hard for me to imagine that I can ever learn to spot a hibernaculum, but I do know black cherry trees, a preferred host, so that’s a start.

The viper’s bugloss (Echium vulgare), a member of the forget-me-not family.

I am happy to find viper’s bugloss, my mother’s favorite wildflower, abundant along the cliff road, nestled against the limestone outcroppings, as impressionistic a combination of pink and blue as one can imagine. The pollen is blue, while the stamens are red. Margaret McKenny and Roger Tory Peterson in A Field Guide to Wildflowers: Northeastern and North-central North America describe it as “bristly.” Yes, it’s the right word. The flowers may look a little fluffy, due to their exserted stamens, but the plant rebuffs touching. It is definitely a porcupine in flowery dress. “Bugloss” derives from two Greek words meaning head of a cow and tongue, the import of that being that the leaves are as coarse as a cow’s tongue.

Close-up of viper’s bugloss, also known as blueweed, showing exserted pink stamens with slate-blue pollen .

Close-up showing bristly nature of the plant.

My mother had a passionate attachment to viper’s bugloss, tucking little sprays of it into vases in her kitchen whenever she could. Maybe it was the blueness that attracted her, because she loved the indigo bunting and the bluebird as well, but I suspect she also sympathized with its bristlyness.

It rains every day, which brings the red eft out of hiding. Once years ago as a child I found one that had been stepped on by me or one of my family members near the garden gate as we arrived for the summer, one of its feet flattened, looking so childlike that I felt like crying. I watched this one undulate noiselessly to safety.

The red eft stage of the eastern newt (Notophthalmus viridescens).

June is hay-making season, and the air in Vinegar Hollow is sweet with the scent of flowering grasses, native and nonnative. I remember helping to make hay stacks in the Big Meadow in the old days when a pitchfork was the preferred tool. Then rectangular bales came along, which were easy to lift, though prickly, but with the advent of the huge round bales of today the farmer needs sophisticated machinery to make and maneuver them into storage. Now I just walk among the grasses on the hills, admiring the delicacy of the myriad grass “florets,” trying to remember what I learned in Agrostology, the study of grasses, as a graduate student in botany at the University of Texas at Austin. I loved the course, but we worked almost entirely with herbarium specimens which took some of the romance out of the enterprise. A floret is a little floral package, which includes a very small flower lacking petals and sepals, but surrounded by two protective scales, the lemma and the palea. Much in the study of agrostology depends on the lemma and the palea. And the awn. The specialized vocabulary needed to described the intricacy of grasses is remarkable.

While each floret may seem too modest to admire, many florets grouped together make stunning inflorescences. Grasses in flower argue for a special kind of beauty. Their feathery stigmas and dangling anthers float and shiver in the breezes, and entire hillsides seem to shift when wind moves through the knee-high grasses.

This week I fell in love, again, with a grass I know by sight but whose name I had never learned. It’s downy, pinkish-purplish above and bluish-greenish lower down. Let’s call it the Mystery Grass.

Mystery Grass. Mike said that he’s always called it feather grass and that it’s one our native grasses.

Helen Macdonald, author of H is for Hawk, in her recent “On Nature” column for the New York Times, titled “Identification, Please,” writes that

There’s an immense intellectual pleasure involved in making identifications, and every time you learn to recognize a new species of animal or plant, the natural world becomes a more complicated and remarkable place, pulling intricate variety out of a background blur of nameless gray and green.

She’s right.

A “blur of nameless” grasses flowering in June in Vinegar Hollow.

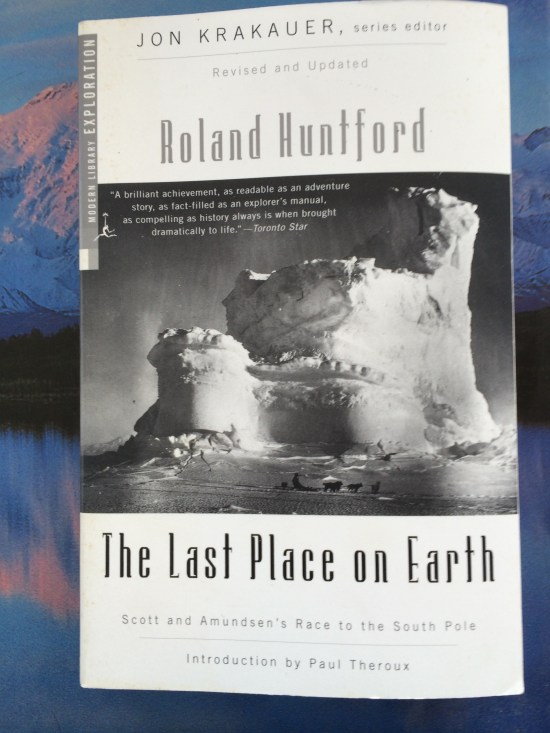

I decided to try to name the sweet-smelling, soft feather grass. I have spent almost a lifetime identifying plants in Vinegar Hollow using Virginia McKenny and Roger Tory Peterson’s field guide, but they don’t include grasses in their book, though grasses are wildflowers. My father taught me the easy forage grasses, like timothy and orchard grass, so distinctive that they can’t be mistaken for anything else, but I don’t remember him naming the mystery grass.

Mystery Grass. Inflorescences open as they mature, allowing anthers to dangle, offering pollen to the wind.

Mystery Grass, showing the purple tips of the inflorescences and a few anthers just peaking out of florets.

Lacking a field guide, I set off into the vast world of the Internet, which after three or hours yielded an answer through a combination of sources: Nuttall’s Reedgrass or Calamagrostis coarctata (synonym Calamagrostis cinnoides). Reader: if my identification is incorrect, please let me know. If I’m right, I’d like to know that also. I never found the perfect source with a clear photograph.

Grasses are hard to get to know, especially as they change through the growing season, similar to birds whose juvenile feathers have different colors and patterns than the adult ones. My “feather grass” will look different at the end of the season, when the seed has ripened. The soft purple will have turned to a whispery tan, and the shape of the inflorescence will change as well. During my search, as I tried to differentiate the “feather grass” from the other grasses common in Virginia, I collected other grasses for comparison. Falling back upon my training in agrostology, I made a multi-species herbarium sheet to reveal the unique morphologies of the inflorescences that in the field “blur” together so beautifully.

Grasses found in Vinegar Hollow, June, 2015.

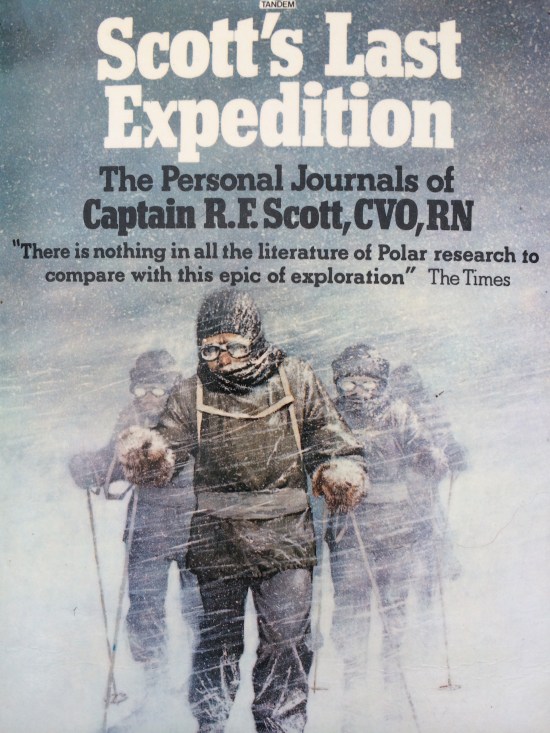

I have other story lines here in the hollow to move forward as well. Two eminent trees, a sugar maple and a black oak, have dominated the farmyard at the end of the hollow for three generations or more. The black oak is all but dead. My father hired someone to put a lightning rod on the oak years ago, but age has overtaken it and limbs are falling steadily. Only a few slender branches have any leaves, and they are small. The granary nearby, full of valuable farm machinery, is at risk. Roy, who has lived in the hollow 91 years, says that it was in its prime when he was young. It is the kind of tree that people stand under and say, if only this tree could talk, the stories it could tell. In high school I wrote a poem for our literary magazine about the trees, which I always thought of as parental, the sugar maple like my mother and the black oak like my father. I had hoped to predecease them, but it has fallen upon me to take action. I met with the tree service this week to make the appointment for removing the oak. As I confronted my depressing role as executioner, I thought of W. S. Merwin’s remarkable piece of writing called “Unchopping a Tree.” No one should take down a tree with a light conscience.

There is good news, however. My husband and I have been protecting two seedlings of this oak in the yard under the electric pole. They must be transplanted this fall before they are too big to move and before the electric company decides to eliminate them. We are going to transplant both and hope that one at least lives for the next 300 years.

Granary and black oak.

Black oak seedling.

The last news story is that the light on the pole lamp went out. Set on top of a tall telephone-type pole, it casts a broad illumination. My mother put it up years ago. She lived at the farm alone for many years and it must have given her a welcome sense of company, and, it would have lighted her chores at night. I never liked it because in the evening it attracted luna moths that would then cling to the pole, quiescent, during the day even as birds pecked them to shreds, and it casts too much light for sleepers who like a darkened room. I wasn’t prepared for the utter darkness that night when the pole light didn’t go on. I had come to the hollow with the dog and the cat, but without the husband, children, or grandchildren. The stars and the moon can be very bright at the end of the hollow, but there are no lights from any other sources. My nearest neighbor, Roy, is over several folds of the creased hills that make up Vinegar Hollow. On this still, overcast night, there was complete darkness without and within, when I had turned off the house lights. Paul Bogard, in his book The End of Night: Searching for Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light, talks about how light pollution affects our relationship with the natural world. Lying in bed, surrounded by complete and utter darkness, I felt a little uneasy, but settled into it, perhaps like a Red-spotted Purple caterpillar in a hibernaculum. I let the darkness take on a natural presence around me.

Then I started thinking about the new stories of this week in June. The cows and calves, the red eft, Nuttall’s Reedgrass, the viper’s bugloss, the black oak, the tendrils exploring the hereafter, and so on. I also remembered one of my favorite reflections about the rural life, made by Verlyn Klinkenborg in his Farewell column for the New York Times’ editorial page:

I am more human for all the animals I’ve lived with since I moved to this farm. Here, I’ve learned almost everything I know about the kinship of all life. The only crops on this farm have been thoughts and feelings and perceptions, which I know you’re raising on your farm, too. Some are annual, some perennial and some are invasive — no question about it.

But perhaps the most important thing I learned here, on these rocky, tree-bound acres, was to look up from my work in the sure knowledge that there was always something worth noticing and that there were nearly always words to suit it.

Klinkenborg kept faith with his column on rural life for 16 years. “Nearly always,” he says, there are words that suit. I pause over the “nearly always.” The work of finding suitable words keeps pulling me forward.