Vinegar Hollow. Stark’s Ridge is the farthest bare mountain top (left of center). Back Creek Mountain stretches off on far top right.

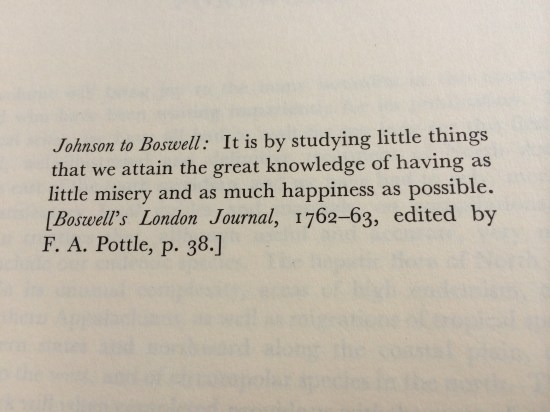

Trekking abandoned logging roads by ATV with a chainsaw in the back of the vehicle is a new experience for me, but happily so. As a young girl I wanted to be a plant explorer in the great tradition of “Chinese” Wilson and Reginald Farrer, who brought back garden treasures from the remotest parts of lands still foreign to westerners at the time. Farrer roamed craggy mountains and misty valleys in Burma, China, and Tibet in life-threatening conditions armed with whiskey and a set of Jane Austen. So here I am, exploring remote mountain tops and glens of the Allegheny Mountains, fulfilling youthful dreams. I am home and do not need to carry whiskey and Austen.

The folds of Back Creek Mountain, which forms one of the north-south borders of Vinegar Hollow, looks impenetrable and pristine from Stark’s Ridge, the highest point directly opposite on the other side of the hollow. The wooded undulations of the mountain range reveal little of the history of human use of the landscape. In fact, it has been logged and relogged for the last several hundred years. Rough trails criss-cross the forest floor in a maze of switchbacks and curlicues. The forest giants are long gone, but secret gardens remain and a hoary pine native to the Appalachian Mountains.

ATVs are bumpy, noisy, and smelly, but they aid enormously in botanizing and can be turned off while one explores on foot. My husband and I had driven up this part of the logging trail maybe half a dozen times, but never stopped to get out at this particular turn in the road. Maybe it was the morning light shining on an expanse of silvery pale green lichens that caught our eyes, but soon enough we were trying to hop about on delicate feet, in thrall to the wonders underfoot in what I am calling the pine cone garden.

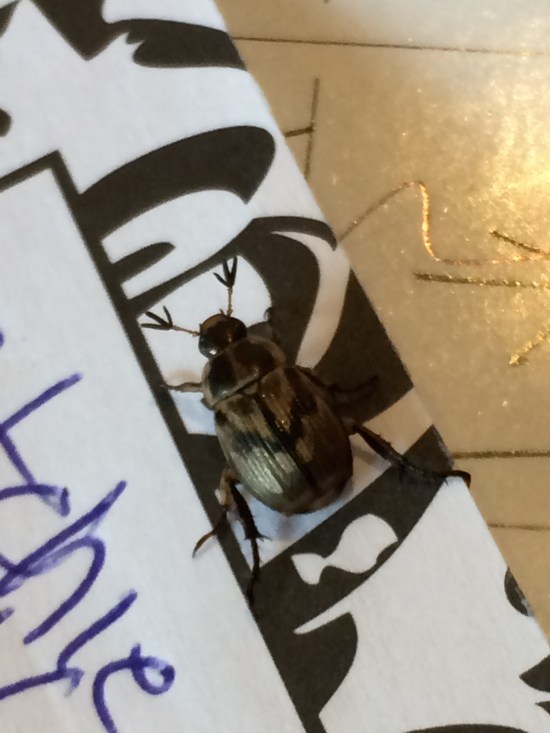

Whether nesting in lichens or pine needles, each cone seemed to be at home. Like sunflowers, pine cones have a deeply satisfying architectural form, the scales overlapping in an arrangement reflecting a sequence of numbers called the Fibonacci series. These cones are striking for their silvery gray brown shading and the curving, decorative prickles at the end of each scale.

The cones are stalkless, seemingly having sprouted out of stout branches.

But where was the parent tree? I looked up finally.

The morning light shone on its lichened, outstretched arms. One branch lay blasted on the ground.

Lichens covered the bark exuberantly.

Further walking on this rocky slope by the side of the logging road revealed some dainty lichens displaying a lovely pastel, slightly orange-pink coloration, something that forest fairies might have planned.

I know I wrote in my last blog about the importance of identifying small life forms, but I decided not to pursue lichen identification here (it would be like Alice falling into a wonderland of splendid but strange forms and vocabulary) because my primary goal now is to honor the pine and its cones. “Hoary lichen” and “lacy lichen” are just my own bland names, not proper common names. It turns out (courtesy of my husband’s research) that the lichen with the pink knobs is easy to identify via Google images. It is known by a lovely common name–the pink earth lichen. Its scientific name, Dibaeis baeomyces, is not at all user friendly. Project Noah offers a photo with a description offering the information that the knobs are filled with “cottony fibers.”

My husband and I got busy taking measurements and assessing characteristics that would identify the pine.

One thing that makes pines fairly easy to identify is that there are not many different species of them in the world. Further, pine needles are arranged in little bundles bound in a common sheath, and the number of needles in the bundle (fascicle) is distinctive for each species. The familiar white pine, distinctive for its long, graceful needles, has five needles per bundle, for example. So, it’s pretty easy to count the number of needles per bundle on a pine sample–we found two needles per bundle in this pine–and look up a list of 2-needle pines in North America. The list is not that long. Also, the pine cones of our pine were unusually prickly, which proved an excellent identifying characteristic. First we settled on Pinus echinata, the shortleaf pine, because it has prickle-tipped cones and it’s native, but its growth habit (overall shape) wasn’t right. We moved on through the list of 2-needle pines.

Voila Pinus pungens, commonly known as the prickly pine, table mountain pine, and hickory pine! Prickly pine is certainly a suitable common name because of the cone, and table mountain because of the high elevation at which it likes to grow, but hickory pine? A hickory tree is in a completely different family and order and is known for its shaggy bark and edible nuts. I love it when the common names of life forms become interesting metaphors, connecting the unlike through some hint of likeness, so I puzzle over its derivation. Hickory trees are often gaunt and gangly in shape, which is perhaps the likeness that inspired the common name of hickory pine because Pinus pungens is described as having a “rounded, irregular shape.” Another possibility is that the common name recognizes the fact that Pinus pungens likes to grow with hickories. However, there were no hickories on this rocky hillside.

It is a lonesome pine. Unlike most species of pines, this pine is known for growing as scattered individuals, rather than in large groves. Lonesome but not unsung. John Fox Jr. made this species famous in his book The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, a top-ten bestseller of 1908-1909, and a book still dramatized in yearly pageants in Big Stone Gap, Virginia where John Fox died in 1919. Fox’s book beautifully describes the Appalachian mountain culture and landscape, and the confusion and disruption that occur when modern civilization arrives, here in the form of the train and coal mining. Fox describes the lonesome pine repeatedly so that it becomes a character in its own right, representing the isolated individual struggling to retain identity. The main human protagonist is a young man from “civilization” who arrives to bring change to the area but is nevertheless sensitive to the value of what he finds there. Fox writes from the point of view of this character:

He had seen the big pine when he first came to those hills—one morning, at daybreak, when the valley was a sea of mist that threw soft clinging spray to the very mountain tops: for even above the mists, that morning, its mighty head arose—sole visible proof that the earth still slept beneath. Straightaway, he wondered how it had ever got there, so far above the few of its kind that haunted the green dark ravines far below. Some whirlwind, doubtless, had sent a tiny cone circling heavenward and dropped it there. It had sent others, too, no doubt, but how had this tree faced wind and storm alone and alone lived to defy both so proudly? Some day he would learn.

–John Fox, The Trail of the Lonesome Pine

He suggests a parallel and a connection between the plight of the lonesome pine and the human being. Defiance in the face of unaccountable whirlwinds, like World War II. My parents loved this book for its description of the mountains they settled in post my father’s service in the war. With all their hearts they aspired to be mountain folk, fierce individuals never at peace when far from lichen-covered trees and forested vistas. Their grandson has now purchased some of this mountain land to protect–from the “green dark ravines far below” to the rocky slopes of the ridge tops where the lonesome pine survives, casting its prickly cones into a garden of fantastical lichen, both tender and tough.