“So, what’s your vote? What’s the most amazing flower here?” a father asked his two young children. He sat on the knee-high edge of a long reflecting pool that ran the length of a stately glasshouse. There was no answer as his children were too busy trailing their hands among the water lilies. It was the second weekend of The Orchid Show: Key West Contemporary being held at the New York Botanical Garden (March 1- April 21, 2014). I was there with my son and grandson, just two.

My son and grandson pointing to different routes in the conservatory of the New York Botanical Garden. The two year old led the way.

“I vote for the jade vine,” the father said, looking up.

I answered the man. “Yes, I agree. The jade vine wins.” After college, I worked for a year at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, UK, as a work-study student. There I met my first jade vine, and came home with a botanical drawing by Margaret Stones that I have carried with me ever since.

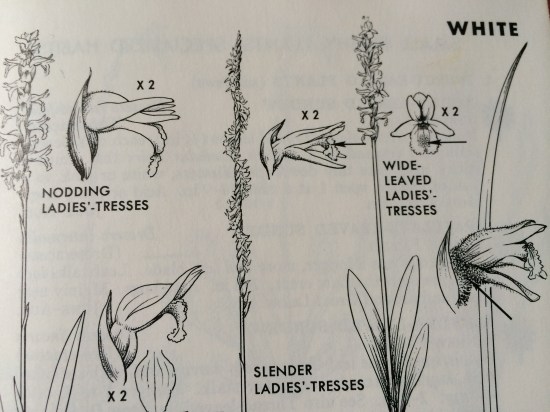

To a budding botanist, Kew Gardens was heaven, but my entry into heaven was rough—and the ordeal was orchid related. I arrived in September for my first day of work with a terrible head cold contracted in the dry air of the British Airways flight over. I still remember the skimpy navy blue blanket I huddled under and how cold I was the entire trip. Mr. Pemberton, the director of students, had said he would put me “under glass” in the orchid house for the first three months because (it was clear during my interview that he didn’t like Americans) he assumed that I was a pampered sort I suppose. (I proved him wrong.) We have heard about orchid thieves and orchid addicts, but has anyone heard the story of a naive, young preparer of orchid potting medium? The supervisor of the orchid house set me to work making orchid “soil.” In my botanizing in Highland County, Virginia as a child I had met a number of orchids, beautiful species like the slender ladies’ tresses, which were terrestrial and hid sweetly among the meadow grasses. I was shocked when I saw how tropical orchids were arranged in the propagating house, attached to little gravestone-like boards, hanging row on row, on the side walls of the greenhouse. The “public” never entered this greenhouse. In the jungle these tropical orchids live as epiphytes high up on tree branches on leaf litter, absorbing nutrients through their peculiar spongy roots that protrude like branches into the air. They don’t live on the ground in soil. However, there were a number of tropical orchids that resided in clay pots on waist-high benches in the central part of the greenhouse. They didn’t need “normal” potting soil, but rather a special nutrient-poor potting medium.

Photograph of drawings of ladies’ tresses orchids (Spiranthes) from Peterson & McKenny’s A Field Guide to Wildflowers (p. 18). The slender ladies’ tress grows in Vinegar Hollow, Highland, County, Virginia.

Making orchid compost with a bad head cold proved to be a nightmare. First, I snipped clumps of dried sphagnum moss into smaller pieces with scissors. Sphagnum moss is a wonderful vehicle for water retention when it is moist, but dry, it’s like fiberglass insulation. Luckily I didn’t know about sporotrichosis, the rose-gardener’s disease, but maybe that’s why I suffered so. Bits and pieces flew around and went up my nose where they tickled and prickled, causing profound irritation. Then I had to separate clumps of charcoal into smaller pieces using sieves the size of dinner plates. Clouds of charcoal dust surrounded me, invading my nostrils and sinuses. The final step was to mix the chopped sphagnum and charcoal chunks with shredded bark. Hooray for shredded bark, a relatively “quiet” substance. After mixing, voila, a suitable substrate to anchor the orchid in its pot where it never wanted to be! I made orchid potting medium for a month and got sicker and sicker. I could hardly breathe and I couldn’t sleep at night for the coughing and snuffling and expectorating of greeny black effluent. Each day when I got on the tube to go to my flat, I looked like a chimney sweep, blackened snot dripping from my nose, my hair gray, my eyes red.

Another treasured momento from my year at Kew Gardens, a print of the wild squirting cucumber (Momordica [Ecballium] elaterium), a copy of an 1842 Burnett botanical print). I met the squirting cucumber in the order beds, where species were arranged by family, and watched fruits explode.

I would say the specimen at NYBG is growing like topsy, as “rampant” and “rank” and “aggressive” (all words applied to the growth habit of the jade vine) as it can get in the still relatively confined space of a conservatory. In the wild of its native Philippines, it can grow to 80 feet and each raceme can carry 100 flowers. But it’s the color that makes you stop dead in your tracks. I think it safe to say that there is no other flower in the plant kingdom so strangely, alluringly, and bizarrely colored. It is like jade, but the hue in plant tissue takes on a startling iridescent sheen. I picked up a blossom that had fallen to the floor and put it in a small plastic address box I carry. By evening the blossom was shot through with the colors of the northern lights– pinkish, pale bluish, lavenderish, pale jadish.

Its shade has been scrupulously characterized in a lovely book published in 1976, Flowering Tropical Climbers by Geoffrey Herklots. The author, botanist and ornithologist, developed a hobby of cataloguing sightings of the great tropical vines of the world and drawing them, beautifully, both in color and in line drawings. For the jade vine, he names three colors with numbers, probably in reference to an artist’s color chart that apply—Jade Green HCC 54/1 and 54/2, Viridian Green HCC 55/1, and Chrysocolla Green HCC 56/1. Interestingly, jade, viridian, and chrysocolla are all mineral stones. There is something mysteriously unplantlike about the color of the jade vine, as if it’s the result of being crossed with a lizard or a chameleon or rare gemstone.

The shape of the each blossom adds to the intrigue. A member of the Fabaceae (Leguminosae) or Pea Family, the blossoms have the characteristic architecture of pea flowers, but on a grand scale. The jade vine’s awkward-sounding Latin name derives from the Greek “strongylodon” meaning spherical and “botrys” meaning raceme or cluster. Grouped en masse, the blossoms’ “claws” or “keels” zigzag swingingly down the stalks, sultry scimitars just looking for a fight. The flowers are the opposite of flimsy, often described as “fleshy” or “waxy.”

The jade vine is losing its place in the wild, although a recent expedition of botanists to Palanan Point in the Philippines has found locations where it still climbs freely. Known to be bat pollinated, specimens have not been happy setting seed in the conservatory setting, but researchers at Kew Gardens have recently enabled a plant to set fruit. A few years ago their website showed a heavy pod attached to the vine with a little help from a supporting macramé like mesh. In Puerto Rico, bees are vigorous pollinators, tearing apart the flowers for nectar in the process. So what is the world’s most beautiful flower? The question is unanswerable. Is it one of the orchids– the voluptuous cattleya? the delicate slender ladies’ tresses? or is it the sea-foam green jade vine flower? (Or is it the peacock’s tail?)

Who is the fairest of us all? That is not a good question, and the young father did not ask that question. He asked, “What is the most amazing flower here?” Yes, the jade vine. It was then in early March, and still now, the most amazing flower at the orchid show at NYBG and the most amazing flower I saw during my year at Kew Gardens. The fairest? Each organism is the fairest of us all. We need every speck of diversity, as E. O. Wilson, the great naturalist has said over and over. Working with plants, in horticulture–sowing seeds, digging, planting, weeding, mulching–has always made me feel grounded, literally and spiritually. Plants have been for me, from a young age, a lifeline to sanity (except for those few experiences mentioned above). I look at each individual plant and feel rooted in partnership as his or her neighbor on the Earth. Support your local botanic garden. Take classes. Draw plants. Write about plants. Grow plants. Weed, yes, but place the weeded gently in the compost. Remember the words on NYBG’s display sign: “After all, plants make life on Earth possible–no plants, no people.” If we are what we need, then people are plants, and, why not consider the reverse, plants are people.