It was 1° in Ithaca, NY, this morning. It seemed cold but then I checked on my daughter’s temperature, she has recently moved to Saranac Lake, NY, and it was negative 15° there. So I felt warmer but overindulged and longed to give some of this excess warmth to my daughter.

There was yet a new dusting of snow. Yesterday morning felt more like being in a snow globe turned upside down by an enthusiastic child, while today a cobweb mohair shawl covered surfaces and crevices. All this month I have been thinking of the cold and the snow, wanting to appreciate winter, understand how it helps us see or not see what is around us. (And if we feel a longing for what we cannot see, this perception should help us remember to love that which is missing when it is right in front of us.)

This reminded me of a favorite text that I used with my academic writing students at Ithaca College, Figures of Speech for College Writers, an anthology by Dona J. Hickey. The readings were all about metaphor, the central thesis being that metaphors are imperfect and paradoxical, concealing and revealing in one tiny phrase. The students and I found a lot to discuss in the essays chosen by Hickey.

The naturalist’s calling is to learn from first-hand experience. This is difficult at 1º, but I have a dog who lives for just that, so off we go several times a day, around the block, if the roads are too bad to get to the country.

I see the tracks of a rabbit out early. I know her in summer, and now I see her hunched in the cold, feet making butterfly shapes.

I see the brown-and-white skeletons of summer’s weeds against the winterwhite of early morning. The snow reveals their delicate structure clearly now. In summer they probably appeared nondescript, without definition, to most passers by.

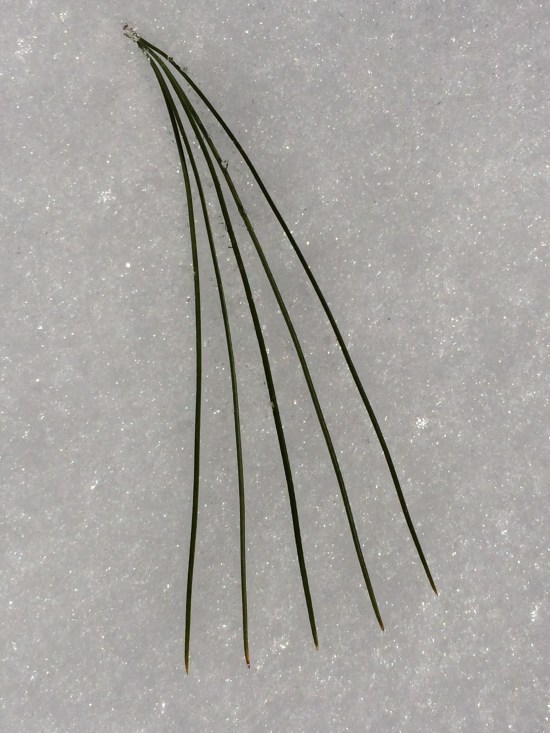

I see the five needles, bundled into a fascicle, of the white pine displayed as if for a textbook. I would not have noticed that fallen fascicle if not for the whiteness of the ground.

I see top hats on the golden-green furry buds of the star magnolia.

I see the graceful architectural sway of the main branches of the Weeping Alaska Cypress (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis pendula) that my husband planted to replace the magnificent multi-stemmed white oak cracked by lightning a few years ago. I was too busy then to document its life and death, but now every time I look at the cypress, I remember to weep for the white oak.

Snow revealing architectural elements of the graceful Weeping Alaska Cypress, with star magnolia to the far left.

I see a part of a tail in the driveway. There’s a tale here I am sure of something that happened in the night…..

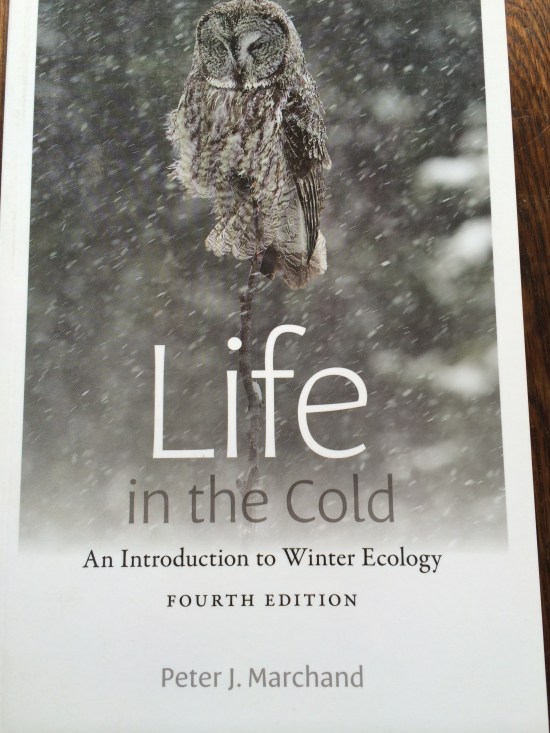

The naturalist does turn to literature to find answers to questions and deepen perceptions. This fall I stumbled on a wonderful book by Peter J. Marchand called Life in the Cold: An Introduction to Winter Ecology (4th edition), published by the University Press of New England. It is a somewhat academic text, but so clearly and elegantly written that I recommend it as pleasurable reading for anyone on a cold winter’s evening.

Last winter I wrote in one of my blogs about how trees adapt to winter, but now I am interested in Marchand’s chapter titled “Humans in Cold Places.” The take-home message is that humans do not have many adaptations for the cold, but they can increase their tolerance, as shown in studies that he describes of aboriginal Australians, the Kaweskar and Inuit peoples, Norwegian and Gaspe fisherman, Quebec City mailmen, Antarctic workers, Finnish outdoorsman, and Tibetan and Indian yogis. This latter group shows some of the greatest ability to exhibit cold hardiness. He writes:

A group of Tibetan Buddhists who live in unheated, uninsulated stone huts in the Himalayan foothills and who practice an advanced form of meditation known as g Tum-mo yoga, show an extraordinary ability to elevate skin temperature in their extremities by as much as 8° within an hour of assuming their meditative posture.

He cites an interesting study showing that yoga-trained army recruits demonstrated greater cold hardiness than physically trained recruits.

Marchand concludes the chapter:

By our cultural and technological ingenuity, we have inhabited the coldest places on earth. Biologically we remain essentially tropical beings.

Tropical? I consider myself more of a north-temperate being as truly tropical climates make me wan and lifeless. Maybe the 64 winters that I have lived through have caused some basic physiological adaptation, but it would be difficult for a researcher to gather data from my experience.

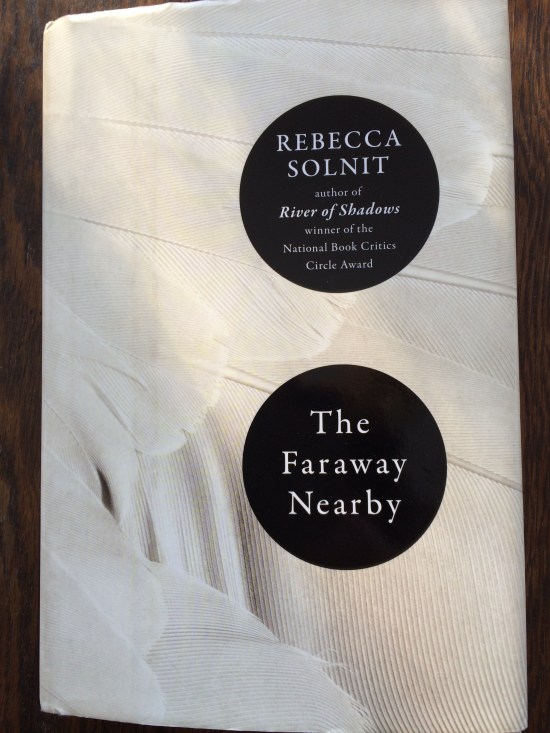

And there are those people who seem to be fatally attracted to cold temperatures. Rebecca Solnit’s new book The Faraway Nearby describes haunting stories of explorers and travelers in the Far North. For example, Peter Freuchen, a young Dutch/Jewish explorer, volunteered to stay in a tiny hut in northeastern Greenland for the winter of 1905/1906 to take meteorological data. He was only 20. His companions left, his dogs were eaten by wolves, and the hut’s interior space became smaller and smaller from the condensation of his breath into ice. Solnit writes:

Before winter and his task ended and relief came, he was living inside an ice cave made of his own breath that hardly left him room to stretch out to sleep. Peter Freuchen, six foot seven, lived inside the cave of his own breath.

Solnit’s book carries many themes, but particularly ruminates about stories that are told and retold and mistold. Tightly woven, the book’s stories will entrance and perhaps frighten the reader on yet another cold winter’s night.

But back to snow as metaphor, for example: snow is a shawl or blanket. Snow cover insulates life in winter, concealing the seeds and roots that will grow in spring. They are there in frozen ground under snow, waiting. Some life forms wait for what seems like forever.

Last year I learned to play, courtesy of my piano teacher, little Fran, who is 91, the very old tune, “Es ist ein Ros entsprungen,” translated as “Lo, How A Rose.” There is a line describing how the rose

“it came, a flow’r-et bright, ___ Amid the cold of winter, When half spent was the night”

(15th-century wording; see Carols for Christmas, arranged and compiled by David Willcocks).

Half spent is our winter here. I will continue to observe snow’s concealments and revelations and sympathize with the cold even as I look forward to my primroses showing up bright in the squishy earthmelt of early April.