Bobolinks. At first it was just a passing acquaintanceship. After all, they are birds, flying by quickly. But now, having spent time in Bobolink Alley and surrounding hayfields, I have become charmed by everything about them, the fact of their bobolinkishness, and, I, a forlorn lover, am mourning their imminent departure for Bolivia, Paraguay, or Argentina.

Like the bobolinks, I am migratory, returning to home territory in Highland County, Virginia. When I am gone, my husband David spends his evenings vegetable gardening, seeing friends, mowing, and bird-watching from a chair in a hedgerow in some hayfields we newly own, which we call Seven Fields. So, I first heard about bobolinks on the telephone. David would rave on about the numbers of bobolinks in the hayfields in Enfield, near Ithaca, and what he was learning about their endangered status. Since then we have discovered that our hayfields are natal territory to a significant number of bobolinks. Watching bobolinks from a distance, even with binoculars, is difficult. They are the usual songbird size, 7”-8” long, and whirl and swirl about with the typical fleetness of such birds, i.e., they don’t pause in prolonged introspection like a great blue heron. David decided to mow a walkway through the middle of the largest, most open of the hayfields in order to observe them more closely. This walkway is Bobolink Alley.

David, Belle (black speck), and Daisy (Jack’s dog) in Bobolink Alley

It is not easy to “get up close and personal” with a bobolink. Bobolinks nest on the ground in the dense undergrowth of hayfields. A hayfield can look serene, a sea of gently waving grasses, but if I make a little noise walking down Bobolink Alley with Belle the dog, suddenly dozens of bobolinks fluff out of the field, swirl and circle to assess the danger, before settling down, invisible once again. They are social and live in loose groups called chains (e.g., like a herd of elephants). The males are polygamous, deigning only to feed the young of their primary female, but other members of the chain help in feeding the young that are not their own.

My husband and I want to keep track of progress in these invisible bobolink nurseries in order to allow the nesting and fledging to proceed without harm. Bobolinks arrive in northern North America and Canada in May. About nine weeks later, mid-July, after fledging their young, they start their journey back to wintering grounds, the pampas of South America. This life cycle is at odds with recent agricultural practices of haying much earlier than in the early 1900s, to reap high-nutrient hay and to harvest several times a season. Mowing too early means loss of nests with eggs; mowing not at all means loss of the only habitat for which they are adapted to build nests. They need grassland. Not shrubland, nor brushland. The Bobolink Project, subtitled “Helping Farmers Protect Grassland Birds,” has organized for the purpose of mediating a compromise between the needs of farmers and the needs of bobolinks.[i]

The bobolink has been called the upside-down bird because of the noteworthy nature of the male’s mating attire. Unlike most North American birds, which are dark on top and light underneath, the mating male bobolink has a dark belly and a prominent “buffy yellow” patch on the back of the head and several bright white patches on the upper wings. While some commentators, like Professor David Spector, author of “Bobolinks: The Poets’ ‘Rowdy Bird’’ has called the attire a “clownish plumage,”[ii] I think that I might make the analogy to P. G. Wodehouse’s young men in love, who often present themselves in a whimsical sartorial manner (e.g., Young Men in Spats). Certainly not classically beautiful like a bluebird, but distinctively bobolinkish. The female bobolink is described as a “buffy yellow brown” (musicofnature.org) or “large pale grassland sparrow” (Spector). “Buffy” seems a word that describers of birds use very freely. I would describe the female as being various shades of medium brown. I would say that the male’s yellow head patch, which is somewhat like the human Mohawk hairstyle, is cream yellow, not buffy yellow! The feathers seem to stick straight up, and the shape of the patch on the rear half of the head is odd.

(On the subject of buffyness, I may be amiss. I have never observed a dead specimen closely, which is not a bad thing of course, but it is hard to evaluate the color of feathers from a great distance [which is why Audubon shot the birds he wished to paint]. I decide to check out the great bird song musicologist F. Schuyler Mathews, a source I greatly respect. While his major focus is bird song as music, he does describe the physical attributes of the birds. I find that he uses the words buff and buffy to describe both male and female bobolinks.[iii] He says the male’s head patch is “corn-yellow” and the middle of the back is “cream-buff” and the female is “brown streaked with buff above” and the “head [is] dark sepia with a central line of green-buff; lower parts pale yellowish buff graded to buff-white”! I take back what I said. The word “buff” or “buffy” is used extensively to describe birds. I have been a plant watcher all my life, rather than a bird watcher, and buff and buffy are rarely if ever used in plant description. However—my husband and I once had an argument about the color of meadows in Highland County in winter sunlight. I said the meadows were tawny [meaning lion-colored] and he said they were dun, a word that sounded a little blah, depressing, and unevocative to me.]

The polygamous habit of the male bobolink necessitates a lot of energetic behavior. A pair of males will erupt out of a quiet hayfield for a competitive chase, settle down, and then erupt all over again, and again, and so on. Professor Spector writes that “A careful study of a meadow with displaying male bobolinks can provide occasional glimpses of [William Cullen] Bryant’s ‘modest and shy’ female that resembles a large, pale, grassland sparrow. She is all business, with no amusing antics. The male, too, of course, is all business, with his plumage, song, and display suited to attracting females—not to amusing us. The humor and clownishness we see is our perception, not hers.” One wonders about the female bobolink’s powers of perception. What does she perceive when she is not the primary female? But perhaps she is the primary female for another male, while being an accessory female for a different male? I am sure that there have been many studies of the mating behavior of bobolinks and it is all very interesting and complicated. But the difficulties of collecting accurate data about who is mating with whom in the bottom of a dense hayfield must be enormous!

Dense hayfield in which much is going on that is invisible to the human eye.

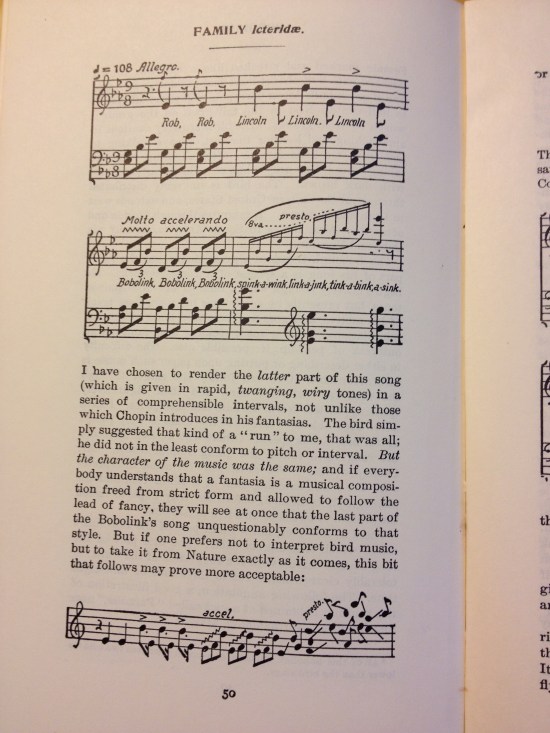

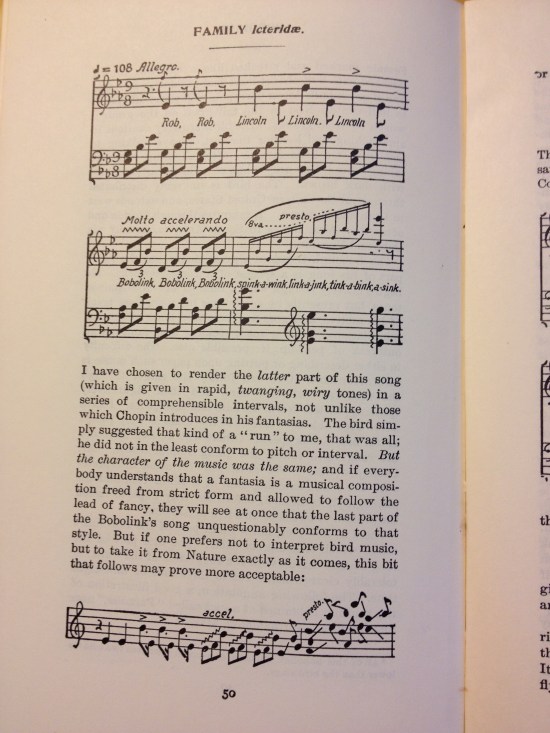

Male bobolinks can sing. Ecstatically. F. Schuyler Mathews, the bird song musicologist I referred to above, writes that “The Bobolink is indeed a great singer, but the latter part of his song is a species of musical fireworks. He begins bravely enough with a number of well-sustained tones, but presently he accelerates his time, loses track of his motive, and goes to pieces in a burst of musical scintillations. It is a mad, reckless song-fantasia, an outbreak of pent-up, irrepressible glee” (p. 49, Dover edition). Another description of its song is “a bubbling delirium of ecstatic music that flows from the gifted throat of the bird like sparkling champagne” (musicofnature.org). The human ear can hardly comprehend the sequence of sounds. I stood in Bobolink Alley a few days ago as a male flew around me. As he flew I turned, and as I turned he circled. Soon I was dizzy. Perhaps that’s the best way to “see” a bobolink, like a spinning top, the scents of the grasses, the clover, the milkweed, the teasel, the vetches, all of it mingling with the male bobolink’s exuberance.

Mathews compares male bobolink’s song to Chopin!

I am always remembering connections to my natal territory in Vinegar Hollow. Bobolinks are related to red-winged blackbirds and meadowlarks, birds that also nest on the ground in hayfields. Once my father came rushing from the orchard meadow, his face solemn and concerned. “Elizabeth,” he said, “come with me. I have something to show you.” I was known, as a young girl, as the resident naturalist. He brought me to Roy, the mower, who stood looking at a patch on the ground. It was a meadowlark’s nest that had been chomped by the blades of the tractor. Some of the eggs lay smashed, oozing yellow yolk. What could I do? I realized that they wanted me to help by witnessing and mourning the destruction of the nest and the distress of the mother circling overhead.

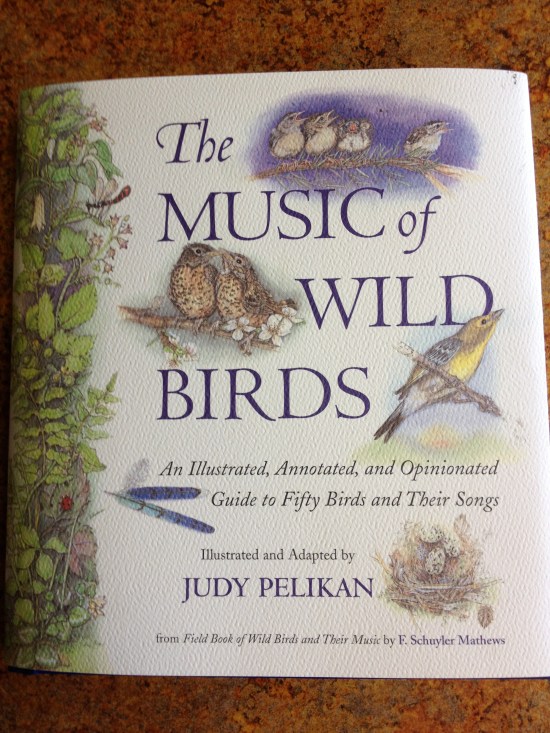

So, a mower at Seven Fields is standing ready, and the bobolinks are about to leave on an incredible journey. It has been recorded that one female bobolink travelled 1,100 miles in one day (wiki). They will come back next May after a 12,5000 mile round trip. I hope. My husband has pointed out to me that they have a characteristic, and unusual, flying style. While most birds flap their wings in a near 180 degree arc, bobolinks never (rarely?) raise their wings above the plane of their body, creating a 90 degree arc. F. Schuyler Mathews is critical of this flying style: “The Bobolink is a distinctive meadow character. He rises from the grass with a great deal more wing-action than the shortness of his flight would seem to demand. It is evident by the constant flipping of the wings that flying is an effort with him, where it is not effort at all with the Barn Swallow. Perhaps his constant foraging in the meadow grass has put him out of practice on the wing” (51-51). Mathews suggests that proof of their shaky flying is that they take the shortest route to South America, hugging land, Cuba and the Yucatan, rather than going over the ocean! Mathews is known for being opinionated, but this criticism is going too far!! Judy Pelikan has illustrated an expurgated version of F. Schuyler Mathews’ original Field Book, published in 2004 by Algonquin Press.

Beautifully illustrated (and expurgated) edition of Mathews’ text.

Bobolinks will be called by other names in different places on their journey: ricebirds in the South where they are shot for their love of rice, and butterbirds in Jamaica where they are eaten because they have gotten fat on rice. Sympathetic sorts, like poets, write about bobolinks, rather than shooting or eating them. Emily Dickinson observed bobolinks in the hayfields around her home in New England (“the Bobolink is gone, the Rowdy of the Meadow”)[iv]and Gertrude Stein, who wintered in South America, made an enigmatic reference to bobolinks in her famous poem “Susie Asado,” a tribute to a flamenco dancer (which made her lover Alice jealous).[v] The line is “a bobolink is pins,” which is not supposed to make any literal sense, but rather musical sense. The entire poem is aflash with “musical scintillations,” to use Mathews’ phrase about the male bobolink’s song. The poem is almost meant to be read as a bird song.

Fledglings in the sky.

I want to be sure that the bobolinks are really ready. My husband and I have sighted groups of fledglings, intermingled young redwing blackbirds and young bobolinks, flitting to the hedgerows, but they are still descending to nestle in their invisible homes in the central parts of the hayfields in the evening. I am worried they don’t want to leave.

Bobolinks: listen for the mower and go.

Belle the dog in Bobolink Alley.

[ii] Available online, published in the Daily Hampshire Gazette, a column entitled “Earth Matters,” a biweekly column from the Hitchcock Center for the Environment.

[iii] Field Book of Wild Birds and their Music (1909), Dover edition.

[iv] See reference in footnote 2.