November 2024: The first snowflakes of 2024 have landed in Vinegar Hollow. They are lying in the pockets of the fallen beech and oak leaves, clinging to the rhododendron leaves, and adding frosting to the landscape. I am also cow-watching from my writing desk, between the fireplace (warm) and the sliding glass doors (cold). I am studying a cow with an orange ear tag and another one seated in profile. She is sitting as snowflakes whiten her coat. In profile she looks like a buffalo or rather a bison. (A recent discussion among biologist friends has clarified the fact that the American “buffalo” is technically a bison, whose scientific name is bison x 3, i.e., Bison bison bison.) A word about bovine terms: heifers are female calves, bull calves are just that, cows are adult females, and bulls are adult males.

Cows in all seasons come up in the late afternoon through the orchard meadow and sit on the opposite side of the fence from garden. For me, it’s a visit that I can count on. They often just sit or stand on the other side of the fence, staring into the distance.I am developing a theory that they are ruminative creatures in more than just the literal sense. Mike, who owns the cows that graze here, says they are just like people, each with their own unique personalities. I was hoping they were a step up from humans because of their grounded lifestyle. In any event, as I eye this “buffalo”-like cow, I see she appears to be chewing in the literal ruminative sense of the word, imperturbable even though there is a winter storm advisory until 10:00 pm tonight. I am glad that she and her companions are near. We have almost constant weather advisories. Two nights ago there was a wind advisory and soon enough a whirling dervish of a storm came howling through the hollow as night fell. It groaned and moaned before abruptly leaving at dawn. I am told there were 300 power outages in the area, but I was spared and felt very grateful to be able to have my morning coffee, as on my previous visit I was without power for nearly 48 hours.

Today when I came back from getting groceries, I met two dawdling calves on the cliff road. They were moving along in a desultory fashion, jostling each other now and again, at ease and companionable. They turned their heads to look at me but didn’t change their pace. So be it. I didn’t want to force them down the steep slope to the left and there was little room on the right, so I advanced slowly but steadily. The smaller one (I believe a bull calf) finally took a dive off to the left—while the larger one stayed his ground and moved to the right. I was able to take his portrait from the car at just a foot or so away. His gaze was direct and calm. What a lovely face! I have often seen groups of calves playing and know they value playmates just like human kids.

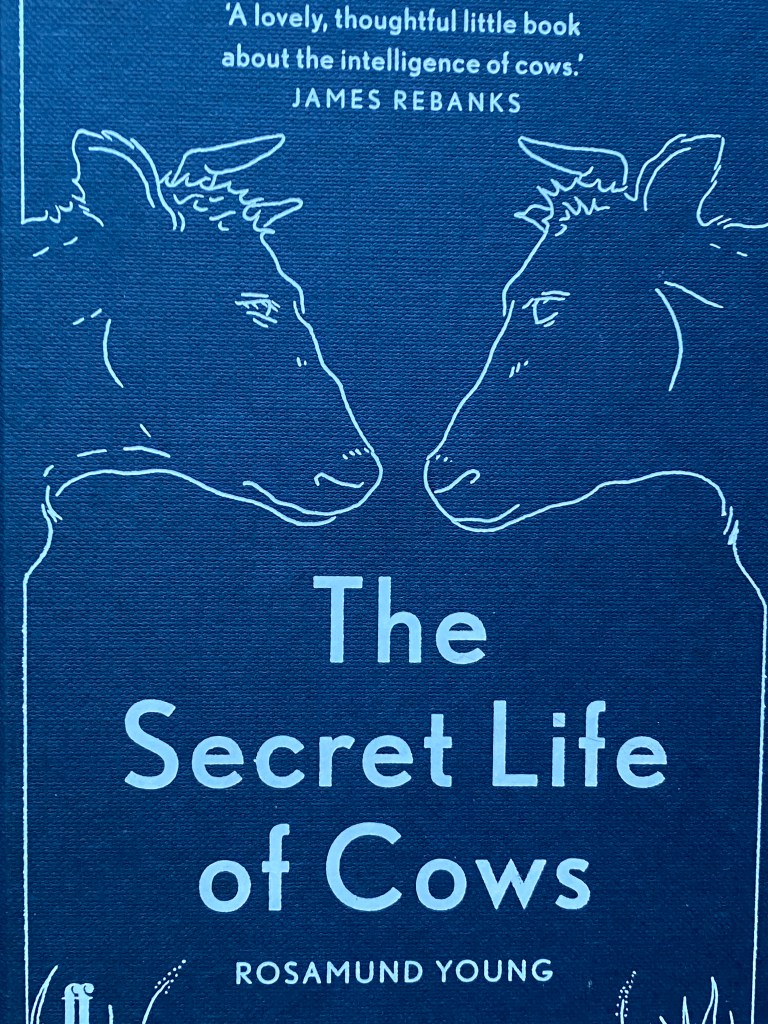

Studying his portrait and thinking about my cow mother friends led me to find a book I had long wanted to read–The Secret Life of Cows by Rosamund Young. First published in 2003 and reprinted in 2017, it is considered a classic in the field of animal observation. Rosamund and her brother Richard and partner Gareth have tended a herd of Ayrshire milk cows on Kite’s Nest Farm near the Cotswold Escarpment for many years. Rosamund tells stories about their cows and other farm animals, persuading readers that cows are just like people, something that Mike has often told me, as I mentioned, based on his experiences tending to his beef cattle in Vinegar Hollow. Rosamund both tells and shows readers that the animals she knows are individuals. She writes, “Just because we are not clever enough to notice the differences between individual spiders or butterflies, yellowhammers or cows is not a reason for presuming that there are none” (p. 3). Her statements throughout are eloquently sensible.

In turn she is able to write about individuals because all members of the herd have names, which sometimes change as events occur in their lives. For example, Highnoon IX became Mrs. Bumble when she produced a “red-and-white bull calf who bumbled about instead of walking, in a cross between a stroll and a lumber” (p. 14). Mrs. Bumble then produced a heifer calf, Miss Bumble, who produced twin heifer calves who were named the Misses Bumble. At this point Miss Bumble became Granny. When Granny produced a tiny calf named Dot she was able to adopt a 2-week old bull calf named Pritchard whose mother, Mrs. Pritchard, had died suddenly. Before Granny was producing milk, Rosamund had been feeding Pritchard by bottle: “Often it would be almost midnight when I trundled up the hill with his last feed, champagne bottles of warm milk clanking at my sides” (p. 43). She describes how her job was made harder as Pritchard hung out in a group of look-alike-in-the-dark calves. There is always plenty of hard work involved in being responsible for the welfare of dependent animals.

In a section titled “Bovine friendships are seldom casual,” she writes “it is extremely common–the norm in fact–for calves to establish lifelong friendships when only a few days old” (p. 59). Thus comes the story of the White Boys, whose profiles appear on the cover of the book. Nell and Juliet produced pure white calves a day apart:”We had never had such white calves: grey, cream, buff, off-white, silvery, golden, but not pure white. The first calf walked over to greet the new arrival and stared at him as if looking in a mirror. They became devoted and inseparable friends from that minute” (p. 59). She writes, “The White Boys lived in a world of their own, in the midst of a large herd but oblivious to it. They walked shoulder to shoulder, often bumping against each other, and they slept each night with their heads residing on each other. They were magnificent: tall, gentle, independent, kindly, though not over-friendly, noble. One had a pink nose, one a grey” (p. 60).

Reading The Secret Lives of Cows was comforting and inspiring–because the author showed me that when humans interact in meaningful ways with other species they create peaceful kingdoms within themselves and for others.

I love visiting with the cows and their calves over the garden fence. They are my main companions as the day goes into night at the end of hollow.