The forest floor in early spring awaiting the arrival of spring ephemerals with foliage of squirrel corn (Dicentra cucullaria) casting shadows.

It was such a long, long, long winter that I am still wandering around dazed by the sudden appearance of flowers all around me. The air carries intoxicating scents from flowers whose shapes and colors leave me wondering about beauty and the question of the “abominable mystery” of flowering plants.

Who is the fairest of us all? Of the many, two have occupied my thoughts. One is an old friend I found in the woods, the Trout Lily (above), and the other an exotic stranger that appeared in my own neglected side yard, the Black Parrot tulip (below), a complete surprise to me.

The earliest wildflowers of the woods are often called “spring ephemerals” because they flower on the forest floor before trees have fully leafed out, when the light is dappled. Everything about the trout lily matches its dappled setting, from the splotched leaves to the yellow brown of the recurved petals and sepals, hence its many other common names like amberbell, fawn lily, adder’s tongue, and dog tooth violet. The coloration camouflages the flower, whose “purpose” is to avoid death before its seeds have matured.

One of the most salient characteristics of their life history is the army of small leaflets that populate their preferred habitat. Once you become aware of the little leaflets of young trout lilies, it is hard to walk delicately enough to avoid stepping on them. There are far fewer flowers.

Elizabeth Murray solved the mystery for me years ago in her 1974 column “In Nature’s Garden” in Virginia Wildlife. She explained the trout lily’s remarkable ability to proliferate and I have always wanted to share it. She writes,

The mature seed lies dormant on the forest floor from mid-summer, when it is shed from the plant, until the following spring. Then it germinates to form a tiny miniature corm which sends up only a single leaf, and no flower. The following season the little corm produces from one to three thin threads called droppers. These sometimes appear briefly above ground and then arch over and burrow straight down into the earth. Each dropper forms a new corm at its tip with the transfer of stored food from last season’s corm. The new corms can be over half a foot away from the original one and several inches deeper into the soil. Each one, again, only grows a single food-manufacturing leaf and no flowers. This process may continue for up to four years, depending on soil conditions, so that there can be as many as 45 plants from the five seeds germinating in one year from a single flower. All of these plants will consist of a single leaf and no flowers and will be spread out over quite a wide area. This of course explains the large, flowerless patches of flowers so often found.Finally, when the corm has reached a good size, it no longer sends out droppers, but instead produces a single, complete plant with the elegant little flower that we know and admire. This unusual procedure helps to ensure vigorous and healthy offspring, since a young plant at the start of its growth will have a large food reserve amassed by the parent. Another advantage one might point out a little ruefully is that the performance helps to protect the plant from predatory wild flower gatherers ! All this “burrowing” embeds the corm deeper and deeper into the soil, so that by the time it is ready to produce a flower, it may be over a foot below the surface. To dig it up without damaging the long, fragile stalk which is growing out from it is an extremely difficult operation.

If you follow her explanation carefully, you cannot help but be impressed by the remarkable ingenuity of this stolon-dropper method of getting around, a kind of vegetative hopscotching. Viable seed are only produced every 4 or 5 years, so this process ensures the multiplication of each crop of good seed.

It is staggering to think of the secret life of these corms, a foot below the surface and the long voyage of the flower stalk up to the dappled light. Please visit WinterWoman’s blogpost with further details and wonderful photographs of the stolons and droppers.

Trout Lily with yellow anthers (anthers are the pollen-bearing organs of the plant). It looks like this flower is shedding pollen. The flower with the reddish brown anthers may be unripe or perhaps sterile. Elizabeth Murray notes that viable seed are only produced every 4-5 years.

The black parrot tulip (Tulipa gesnerana dracontia) is an entirely different kettle of fish in terms of beauty. The group that appeared in the dusty neglected bed next to our driveway, appeared beak by beak, before opening to flaunt their dressy selves among the simple ferns and lily of the valley that eke out a pretty dry existence under the broad eaves of the house. I stopped planting tulips 30 years ago after the deer ate 40 tulip blossoms just as they were about to open. I left for work one morning admiring my long row of perfectly formed blossoms waving gently on glaucous pale green stems. When I came home, there were only stalks two inches high. So, since I do not plant tulips, these wild parrots must have been leftover bulbs from my husband’s garden center planted unbeknownst to me.

The black parrot is apparently so named because their buds resemble the beaks of parrots. This is true. The buds are not very pretty. Parrot tulips develop from spontaneous mutations but were not coveted because weak stems caused the frilly flowers to flop in the mud. A stiffer stemmed parrot mutation called ‘Fantasy’ appeared in 1910 that led to the eventual breeding of the well-stemmed Black Parrot, introduced officially in 1937 by C. Keur & Sons. It has been named the best parrot tulip of the 20th century!

The black parrot tulips seduced me feather by feather. I have no view of the side of my driveway from inside the house, so I was happy to find that they make long-lasting cut flowers. I kept drifting into the room where I left the vase, ogling, considering, wondering, adjusting my view.

Their appeal is exuberant extravagance. Words used to describe the petals include ruched, waved, feathered, frothy, frilled, twisted, scalloped and curled. The color is a deep bluish burgundy, a purple black shot through with green. As the horticulturalist Maureen Gilmer writes, the black parrot tulip “dares to be different, wearing its satins and sequins, even when accomplishing the most pedestrian task” –like adorning my driveway.

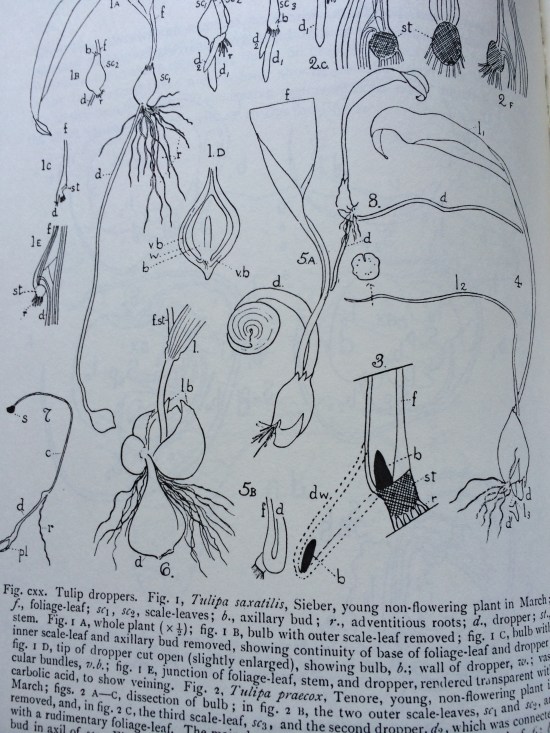

The tulip produces droppers as well, as described in Agnes Arber’s great book The Monocotyledons. Arber, the first female botanist elected to the Royal Society in 1946, and the first woman to receive the Gold Medal of the Linnean Society for contributions to botany, writes:

A curious feature of the life-history of the Tulip is the lowering of the bulb into the soil, year by year, during the period of immaturity. This descent is accomplished by means of a tubular organ, the “dropper” or “sinker,” which carries the terminal bud inside its tip. We may illustrate the first stages from the seedling of Erythronium which behaves similarly.

This page of intense packed squiggles from Arber’s Monocotyledons illustrates her patience and skill in portraying the morphological complexity of the droppers in various stages of development. Fortunately, her father, who was an artist, saw that she had drawing lessons from the age of 8.

How much more we would understand about plant life if we worked at drawing the developmental stages of plants from a young age. Arber’s drawings inform us about form and function in ways hard to decipher when dazzled by the three-dimensional reality of the living plant.

So, who is the fairest of us all? No one can claim that title, because the appeal of beauty is a mystery–one that English professor Elaine Scarry explores in her book On Beauty and Being Just. A distinguished Professor of Aesthetics and Theory of General Value at Harvard, she writes with elegant simplicity and clarity about the value of beauty. I love this sentence:

How one walks through the world, the endless small adjustments of balance, is affected by the shifting weights of beautiful things.

By beauty she does not mean perfection. The army of trout lily leaflets marching higgily piggily over the forest floor is a beautiful, but untidy, sight. One of her theses is that academia has undervalued beauty because it thinks that honoring beauty detracts from an interest in social justice. As the title of her book suggests, she does not agree.

But the claim throughout these pages that beauty and truth are allied is not a claim that the two are identical. It is not that a poem or a painting or a palm tree or a person is “true,” but rather that it ignites the desire for truth by giving us, with an electric brightness shared by almost no other uninvited, freely arriving perceptual event, the experience of conviction and the experience, as well, of error.

If we are aware, every flower, every pollinator, every little one of the “endless forms most beautiful” (Darwin again) should move us to a desire for truth and justice and considering error in our judgment. She believes that “constant perceptual acuity–high dives of seeing, hearing, touching” help us “in the work of addressing injustice.” Barry Lopez, honored in an earlier blog, would agree that this is the work of naturalists.

Charles Darwin called the sudden appearance of flowering plants (angiosperms) in the fossil record 100 million years ago an “abominable mystery” because it conflicted with his theory of the gradual evolution of life forms. He suggested that perhaps intermediate fossil forms might eventually be found in faraway places of the world. In fact, this has turned out to be true. Very early angiosperms have been found in China, remote at Darwin’s time when paleobotany was in its infancy, but now also in Europe and the United States. And a living link between the “primitive” gymnosperms and the “advanced” angiosperms was identified in New Caledonia in the form of Amborella trichopoda, the only member of the Amborellaceae family. It is an insignificant treelet with insignificant flowers, four small, hue-less petals, whose entire genome has now been sequenced in the Tree of Life Project. Although the origin of flowering plants is no longer an abominable mystery, biologists still debate theories to account for the great success of angiosperms over gymnosperms. One is the nutrient-advantage hypothesis—that angiosperm leaves having more veins than conifer needles and scales can draw more sustaining nourishment from the Earth. Flowers persuade me, though, that beauty has a biological force.

Another one of Scarry’s theses is that beauty prompts replication, for “Beauty brings copies of itself into being.” In her wonderful discussion of Matisse and palm tree leaves, she writes “But beautiful things, as Matisse shows, always carry greetings from other worlds within them.” A bulb seller posted Georgia O’Keefe’s comment on their website: “When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world for the moment. I want to give that world to someone else.” That is why naturalists write.

p.s.

The naturalist occasionally has mundane errands, like choosing a new lighting fixture for the kitchen– all the while thinking about Elaine Scarry’s ideas about beauty replicating itself–and there was a painting of a black parrot tulip for sale on the wall of the store among the lights, proving Scarry’s point!

Once again I have loved reading your work. And I love trout lilies, although I have seldom seen them. You know, the entire work of this blog is very special–educational and intimate at the same time. Thank you again.

And I thank you for reading! I think I am getting more long-winded as I go on, which is more demanding of readers, so I thank you for spending the time. E

I went for a walk in the woods today, and found a large number of mysterious white “roots” that looped up out of the soil and back down again. Because I’m familiar with these woods and knew that there are massive colonies of trout lilies here, I suspected that there was a connection, but it still took me quite a bit of Googling with different key words before discovering that these were in fact stolons! Even after knowing the correct word, I could only find a single image on the entire internet of a trout lily stolon. I’m so grateful to have found your posting, and grateful that you took the time to type up a 1974 column! I was motivated to post a photo of the stolons on my very neglected blog, which I think will be linked to my name when I post this comment.